Poignant poesie and a devastating discovery.

A deep dive into the fate of a Jewish family and friends near Dortmund, 1922-1943.

Dear Friends and Followers

Some of you I know, and I guess have vaguely in mind when I am writing, but many of you have just subscribed via an ‘also subscribe to…’ button and you don’t even know that you’re going to get an email from ‘My Teenage Diary’ – so, welcome to your first email if that’s you. I now have over 500 subscribers, which feels rather incredibe. I know we can’t read everything we receive from Substack, but I hope I can entice you to read on today. This one is going to be poignant, and long, and involves an exploration of a historical document. And you’re the first people to hear this story.

Generally, between these newsletters, the question builds up in the back of my mind, what do I want to write about next? What grabs me? What fits with what I’ve written before? What could someone enjoy reading? Then along comes something that clicks. In this case it’s a big click.

I’ve always been curious about old documents and the individuals named in them. Who were they? It could be an old title deed of a house from the eighteenth century written out in spidery writing; I decipher the names and the property and then start an online search to try to find them. I once found a 1969 book of poems in French by the curiously-named “Princesse Zouina Benhalla”, who turned out to be a fascinating, half-Berber writer and performer. What about a cardboard delivery box from Debenhams from the 1950s with an address on it? Surely that needs to be reunited with its address? The house occupier would treasure it and not chuck it in the recycling - wouldn’t they? For example, what would you do with this?

All of which is to say, I’m a bit nosey. And sometimes that’s a good thing. We can’t know everyone’s story of course. But as more and more goes online, we can find out interesting things that help us retell stories that would otherwise be forgotten.

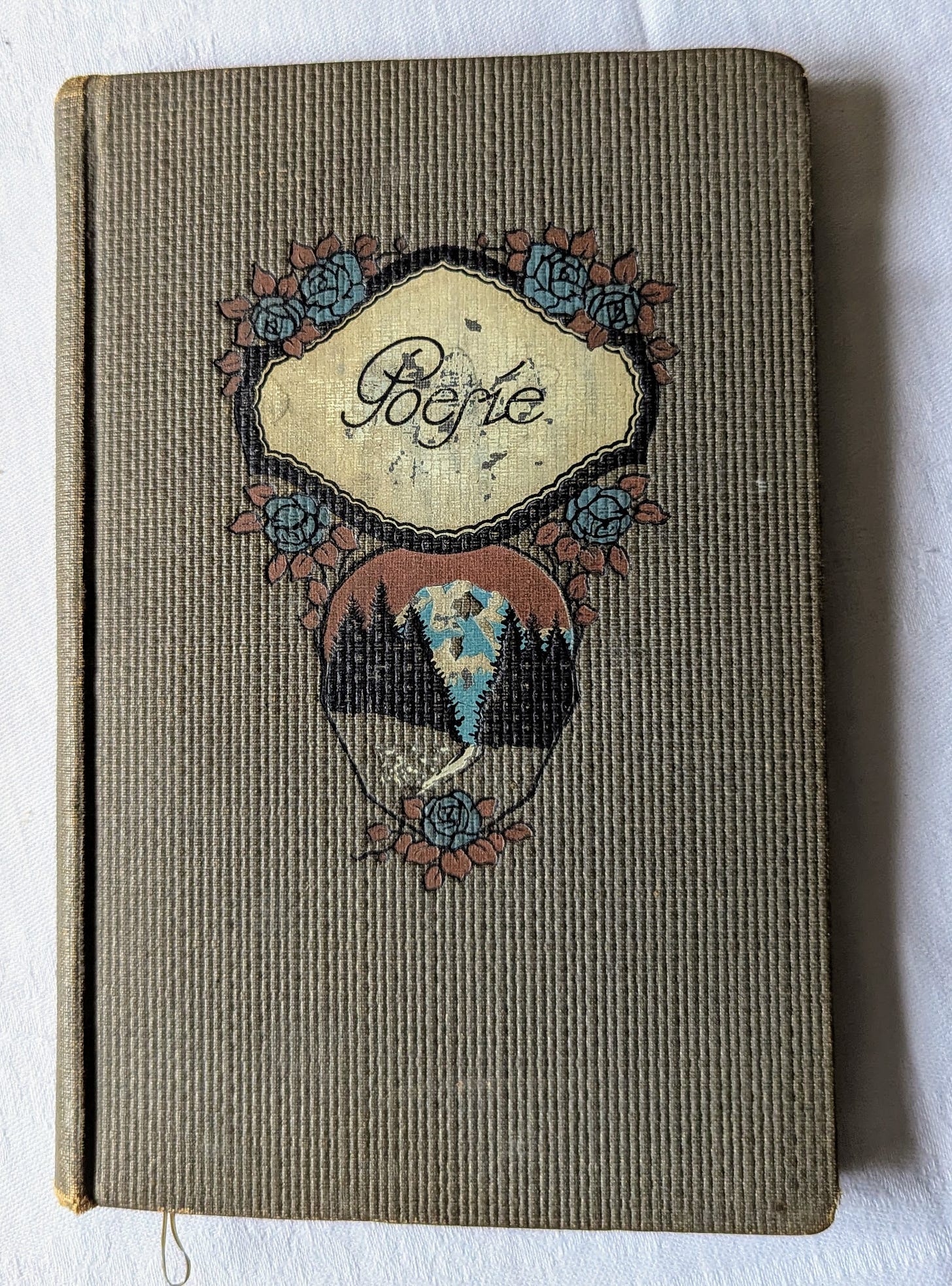

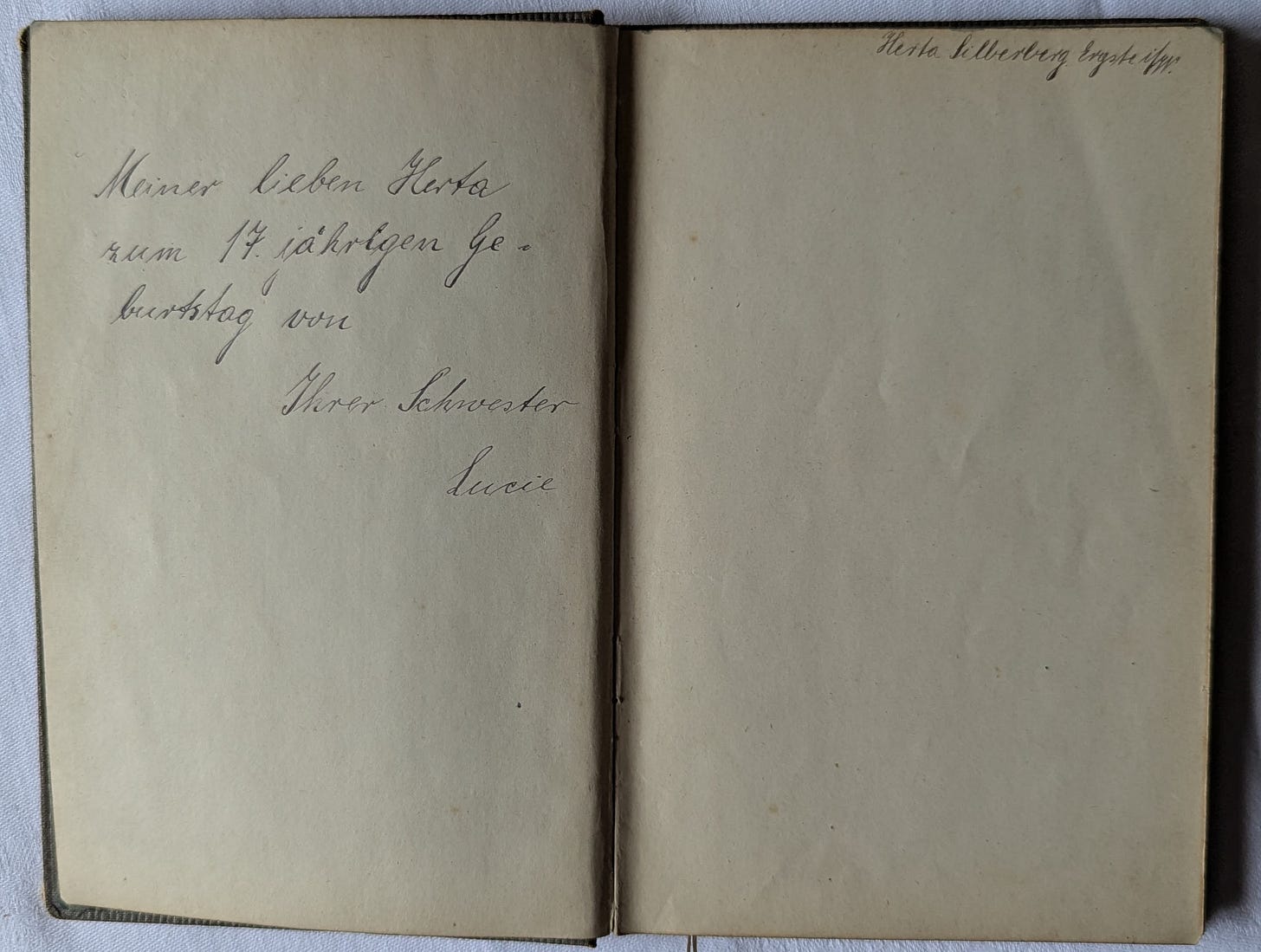

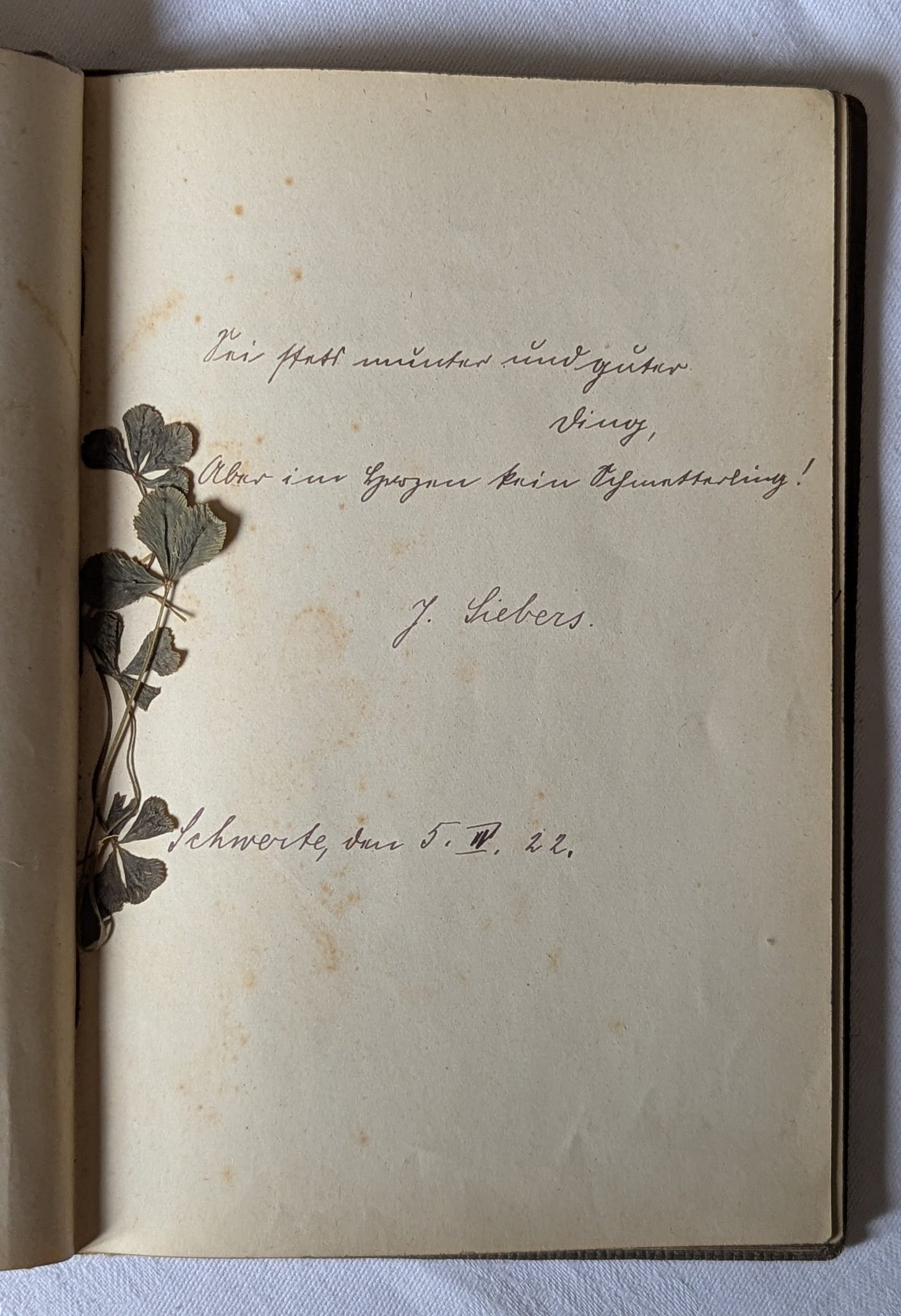

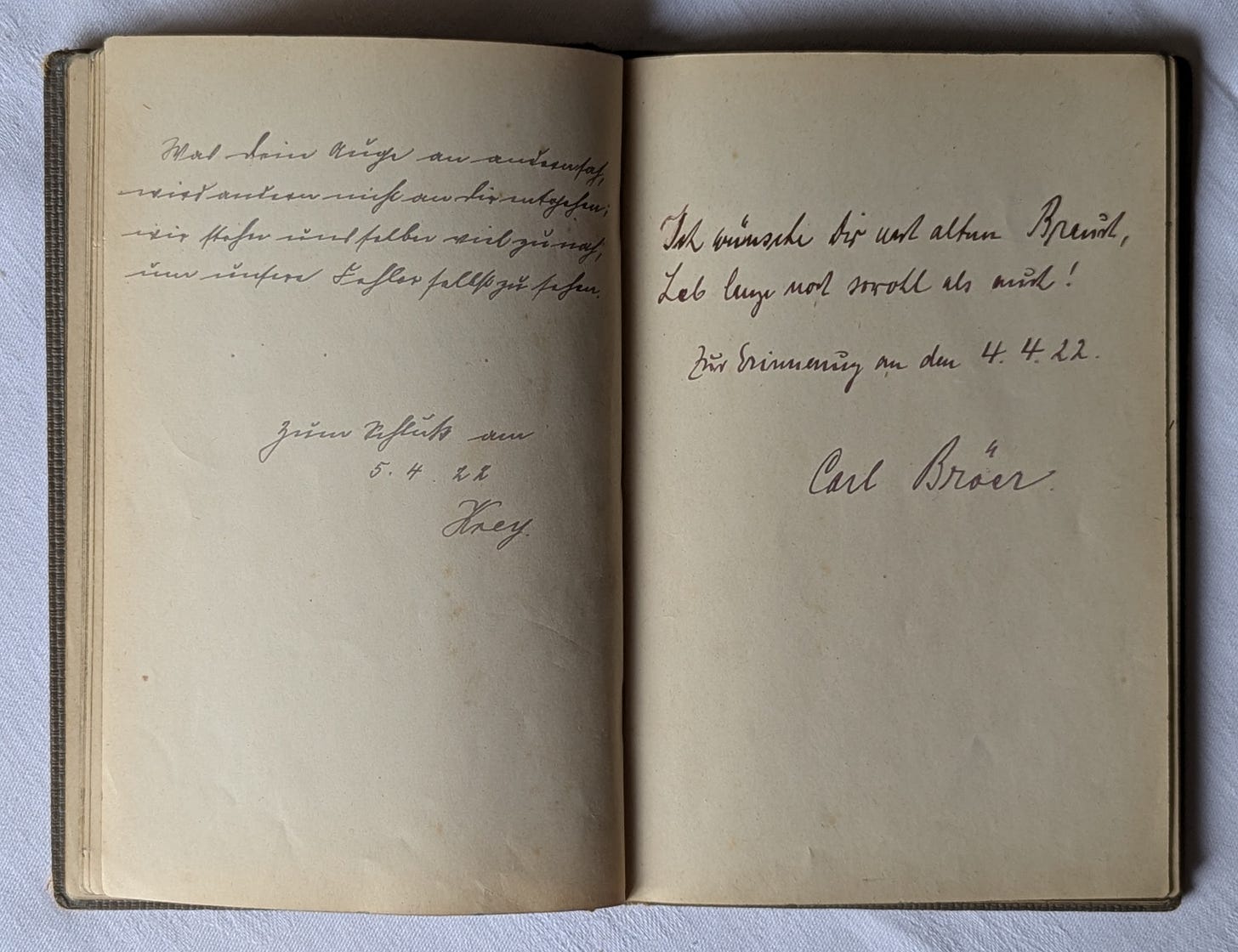

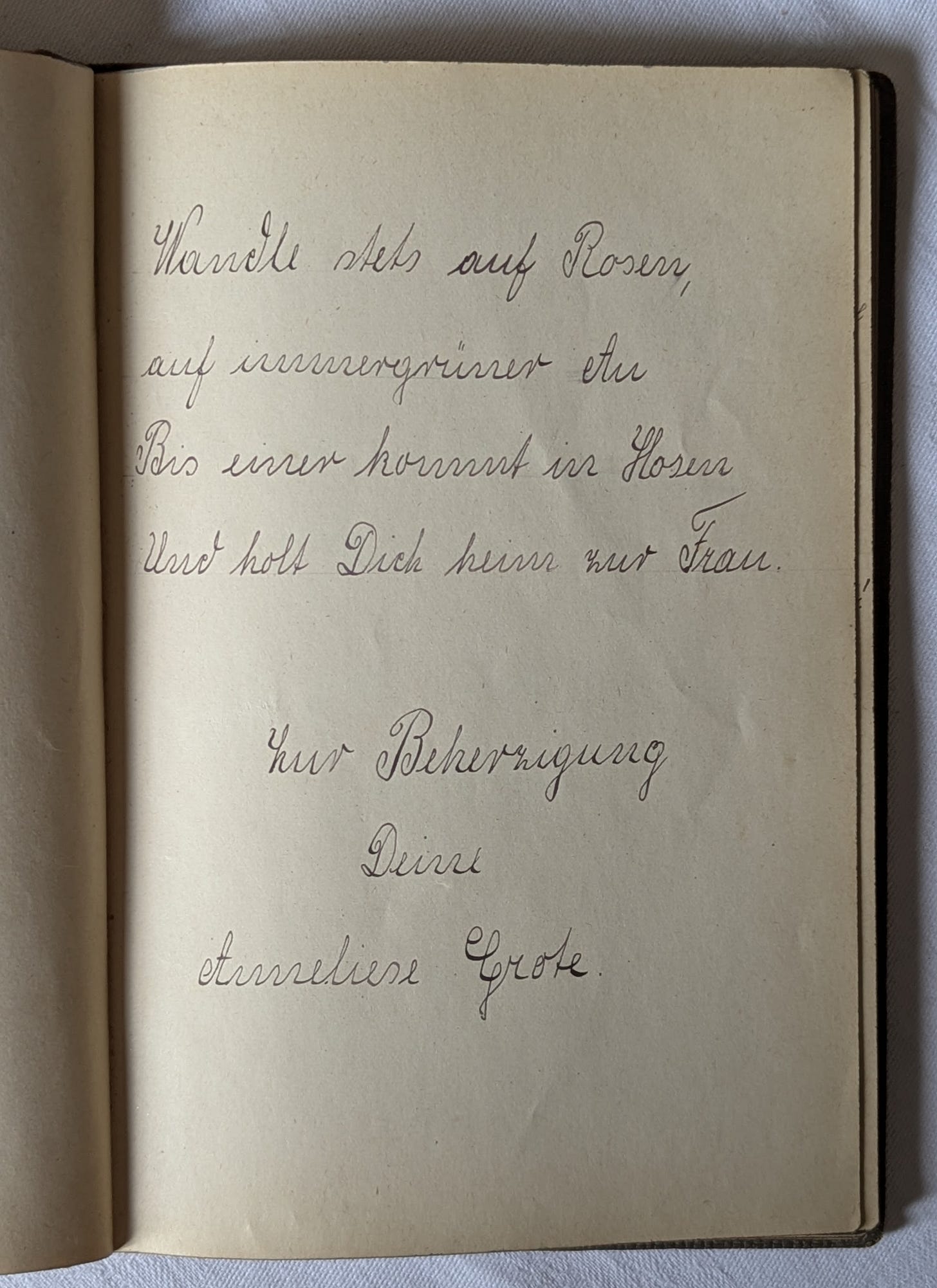

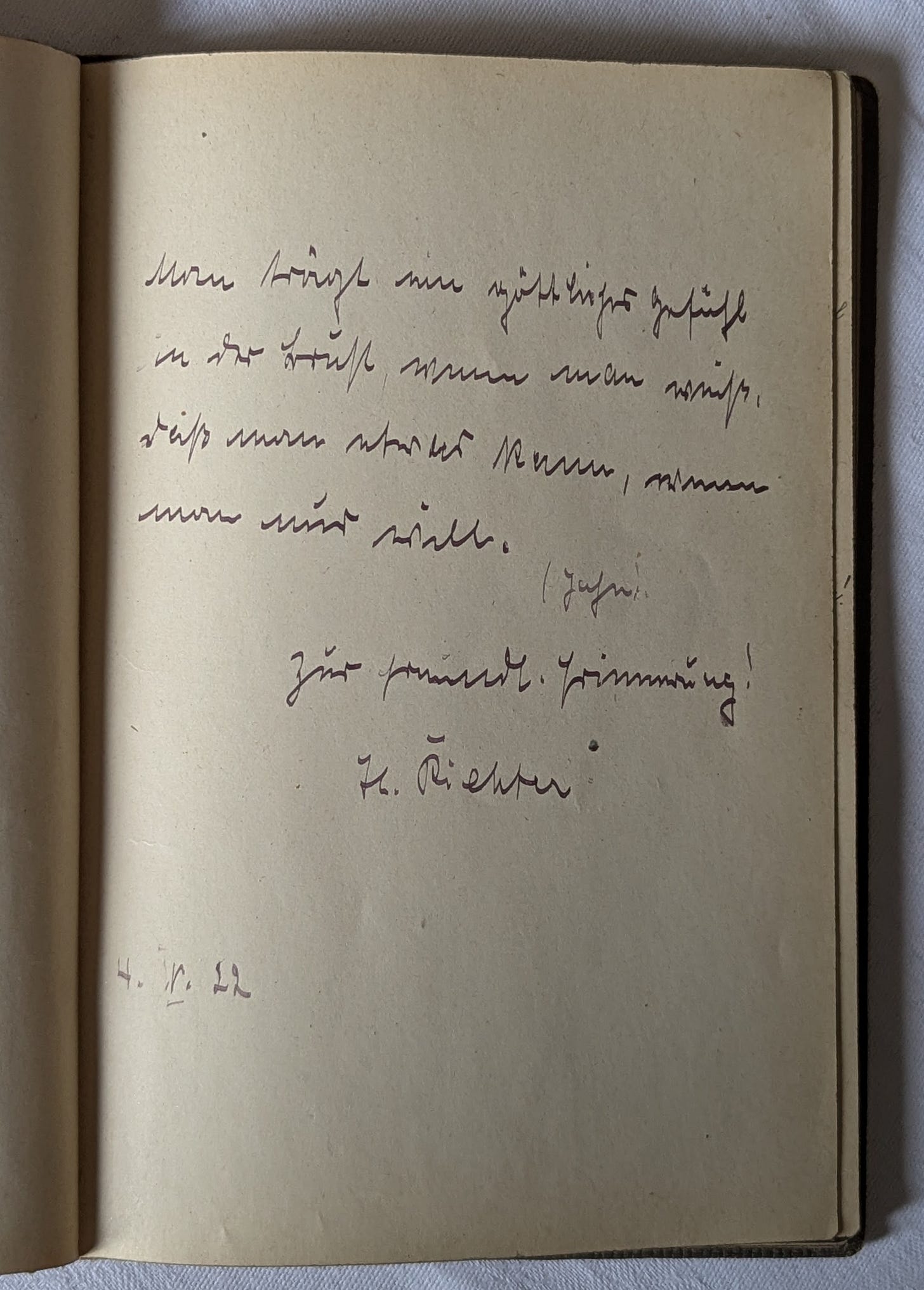

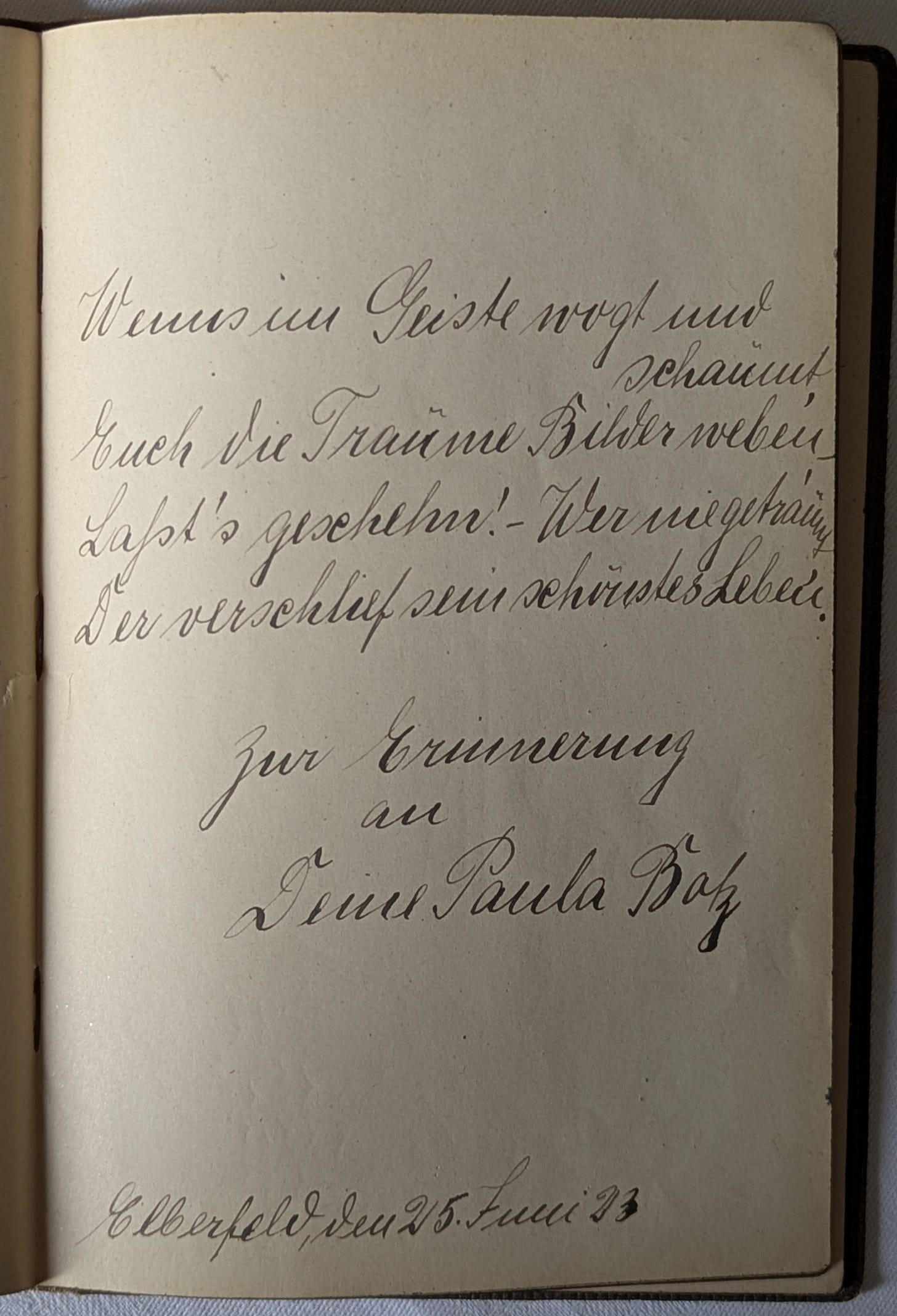

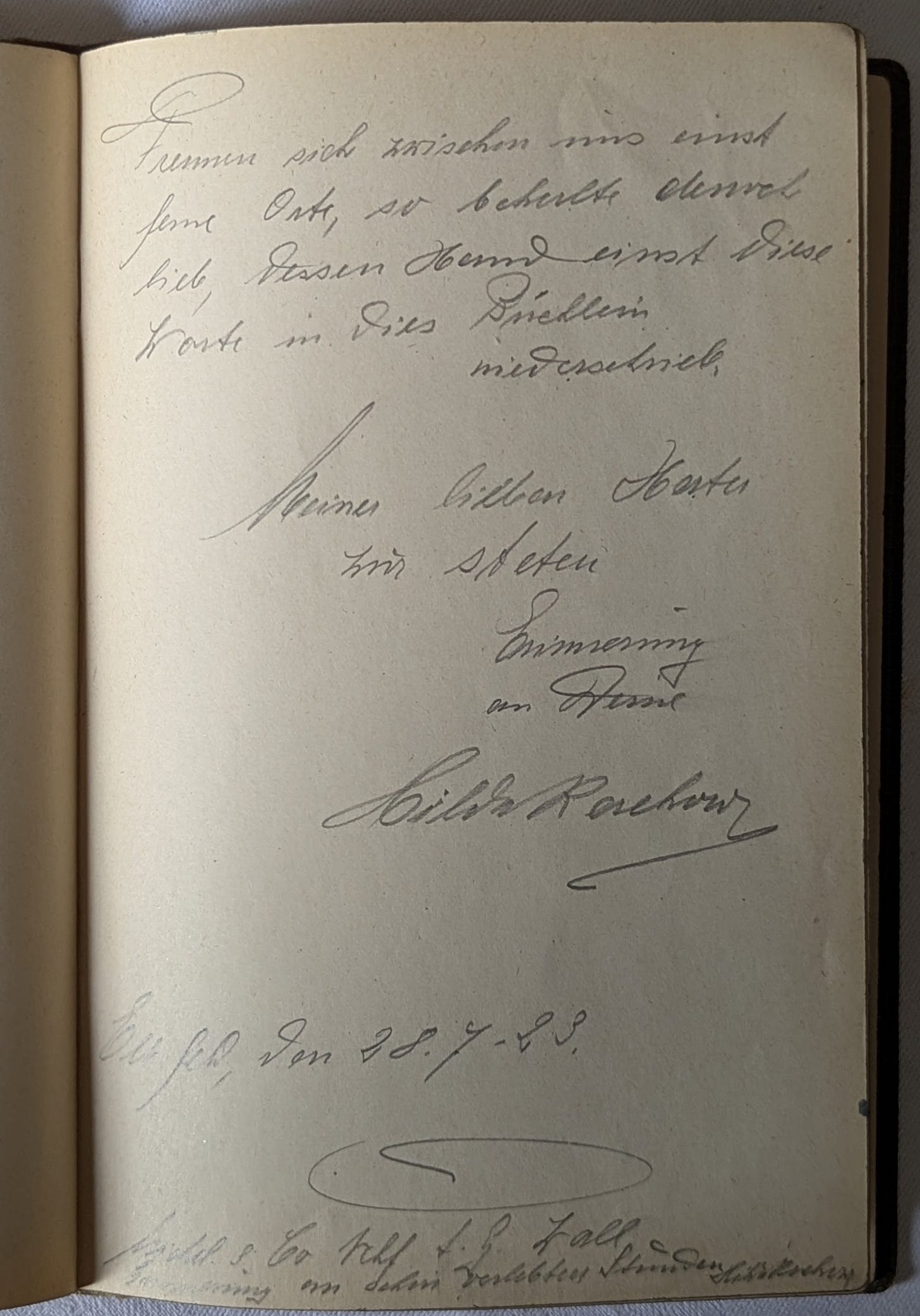

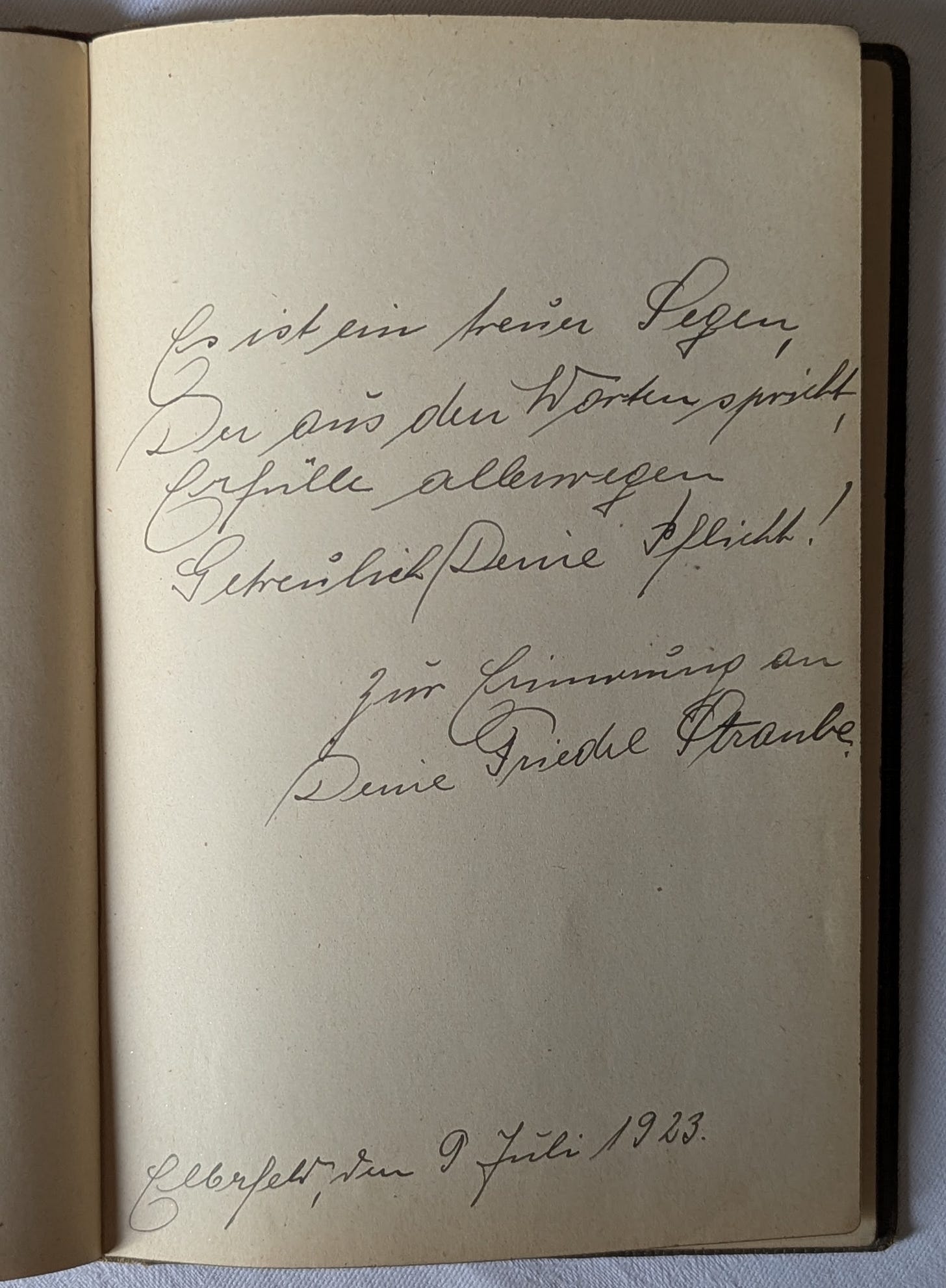

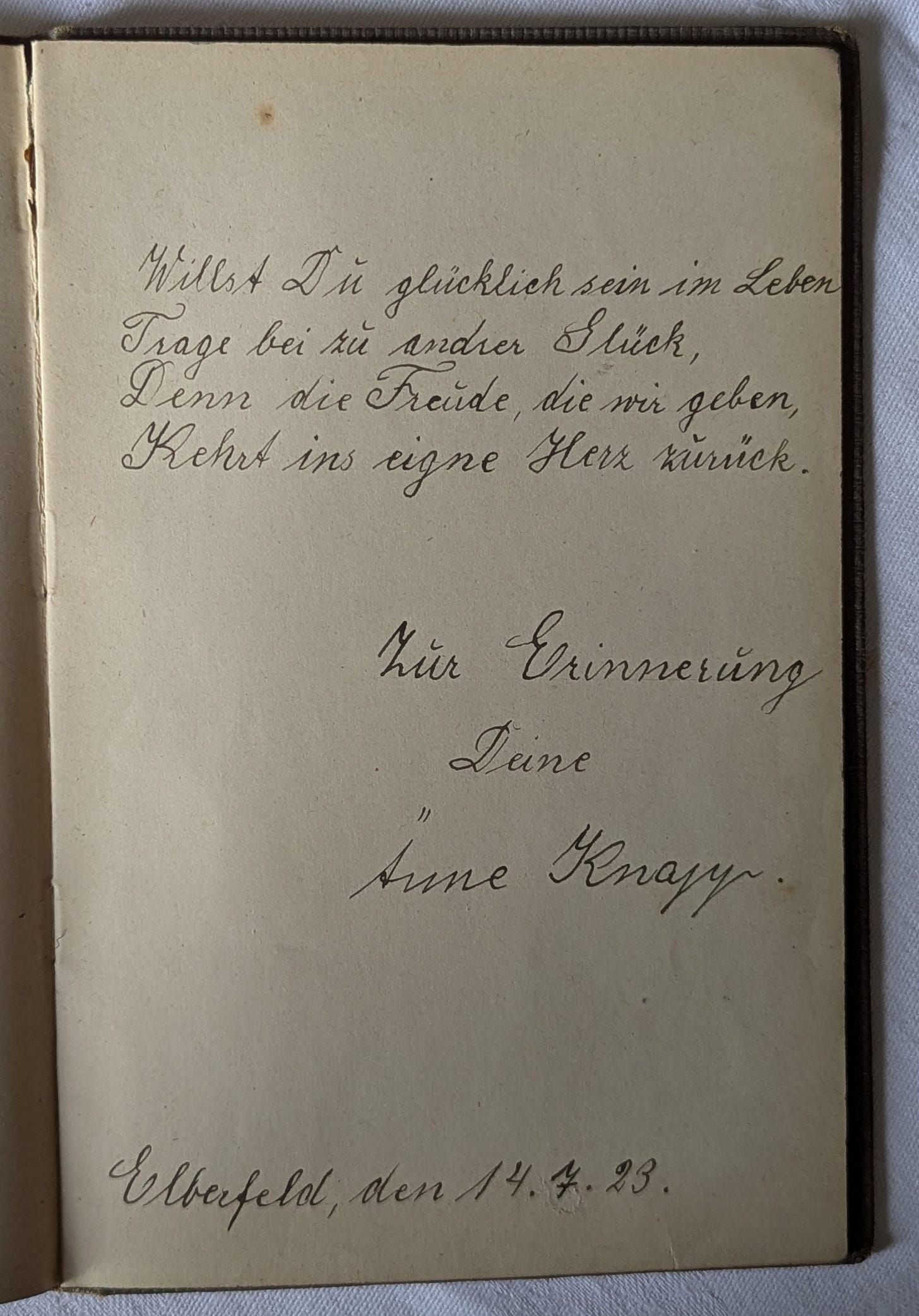

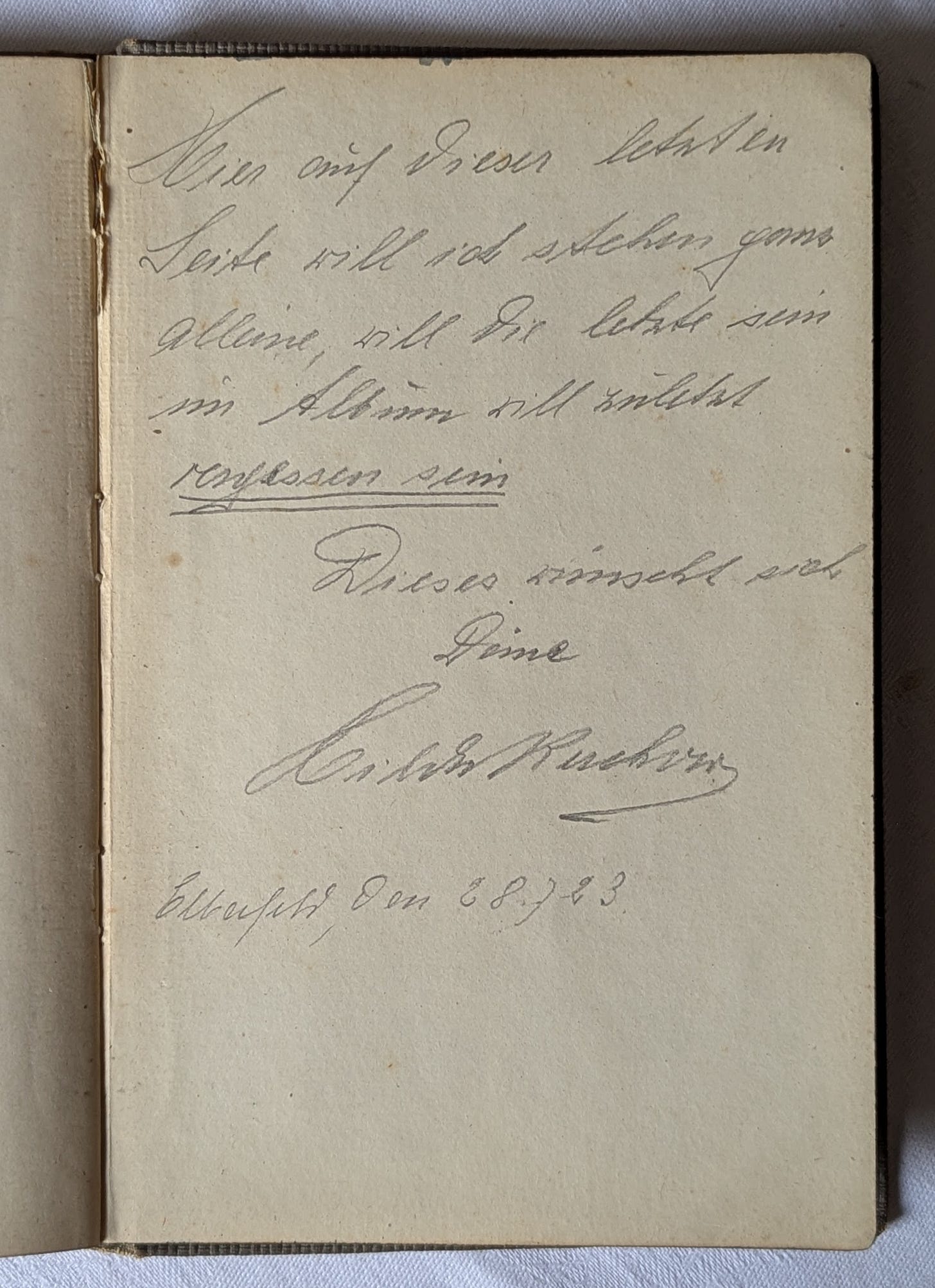

Recently at my mum’s, I picked up a slim little book that, in a rearrangement of some shelves, had found its way onto a tabletop. My mother is a great preserver of random history. I could do a year of Substack just sending you pictures of magazines from the 1980s and before that are lying around the house. And it’d be interesting. I’d seen this little book before. Entitled “Poesie”, it’s a blank book that had been given to a young seventeen-year-old German girl by her older sister for her birthday on, it seems, 24 November 1921. It was to be filled by her friends and family with verse, poems, dedications and kind words for her to remember them by. I was talking with a German-Hungarian friend the other day, who said he’d had a blank poesie book given to him when he was 11 or 12; apparently it’s a thing in central Europe.1

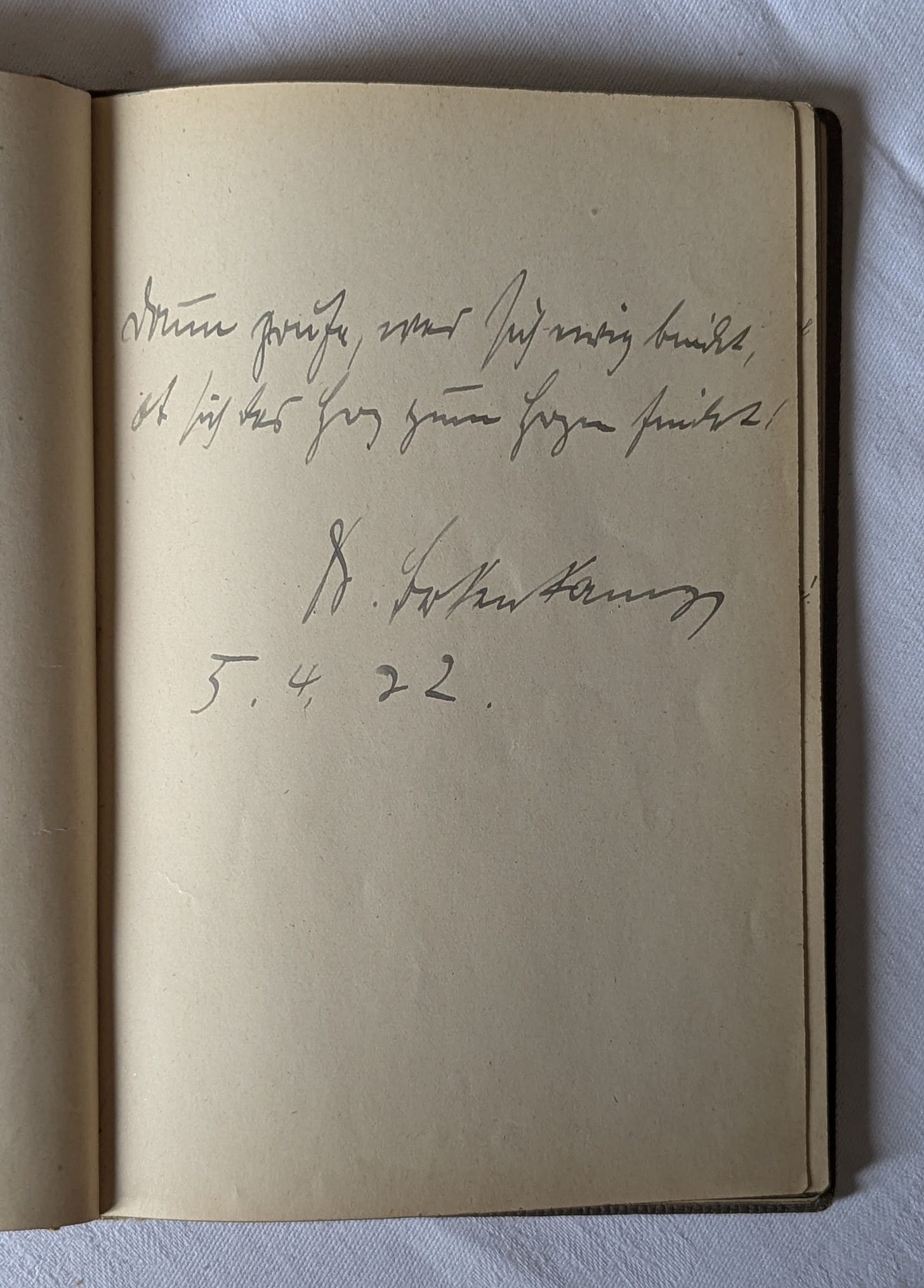

German handwritten script of that time can be quite hard to decipher. Some is rather ornate; some is jagged and looks like someone has just written ‘Mmmmmmm’. That meant I’d previously not really had a proper read. Had I bothered to decode the script, I’d have found a bunch of rather sentimental, clichéd verses. I might have read one or two and then closed the book as not worth much of my time. But context is everything, and in the right context even the most hackneyed, trite words and platitudes are full of potent, important meaning.

So, being nosey, I opened the inside cover and read the dedication. And suddenly everything changed. The context became suddenly clear. I sat up alert, opened my phone and started searching the internet.

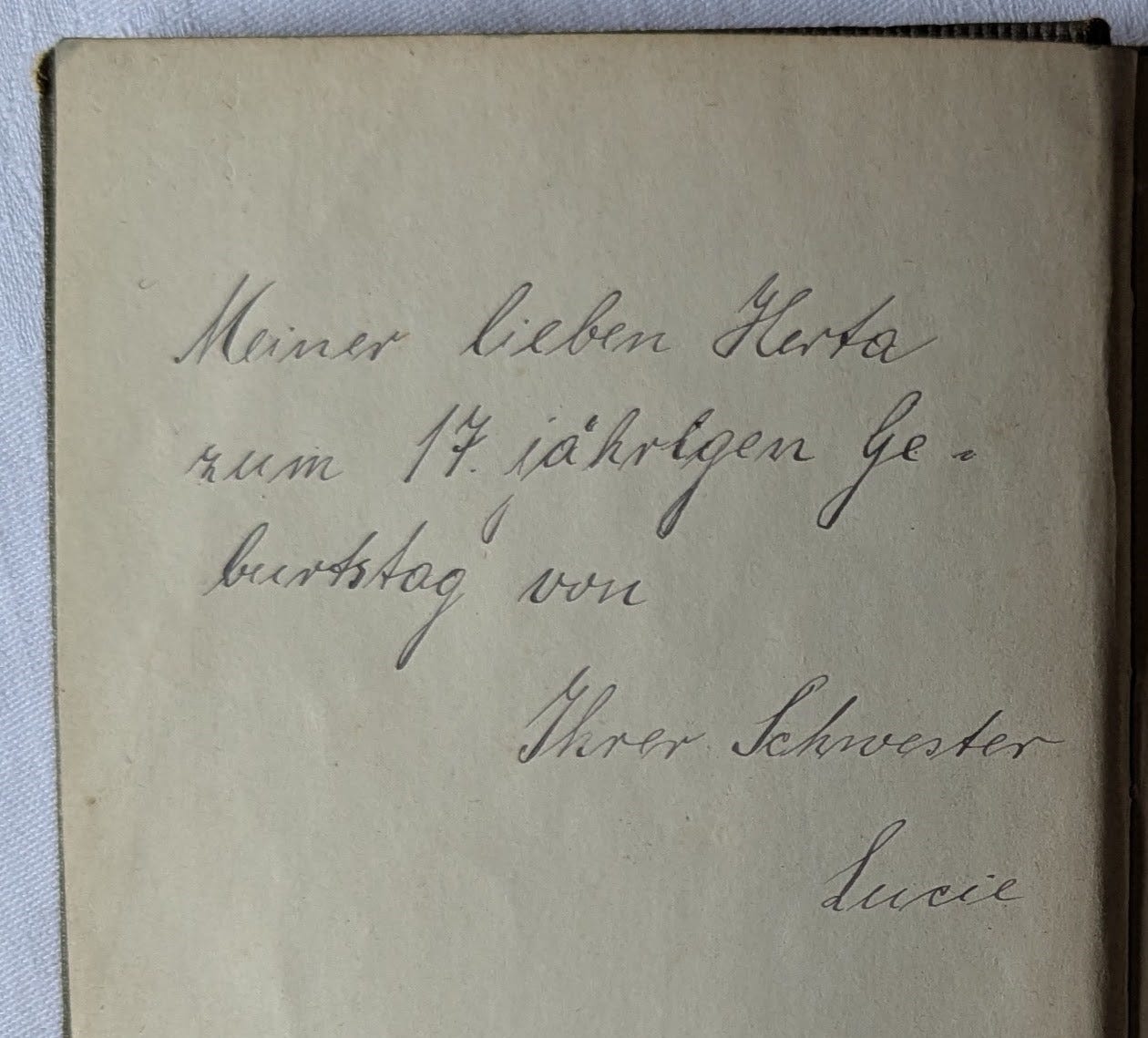

“Meiner lieben Herta zum 17 jährigen Geburtstag von Ihrer Schwester Lucie”

To my dear Herta on her 17th birthday from her sister Lucie.

And on the opposite page Lucie’s 17-year-old sister had written her name:

Herta Silberberg, Ergste usw.

Silberberg. A Jewish name. She was 17 in 1921. What had become of her? There could be a record online.

A search for Herta Silberberg threw up someone who had died in Lodz ghetto in Poland but had been born in 1889. Not her. Herta, 17 in 1921, had been born in 1904. Then I found that Ergste, mentioned next to her name, is a small town near Dortmund in Germany. And when I searched for her sister Lucie Silberberg, who had given her the book, it all became horribly clear. Among the very many Silberbergs listed in Holocaust memorials was this:

Lucie Silberberg

Born 27. 07. 1898

Last residence before deportation: Ergste, Kirchstraße Nr. 19

Transport X/1, no. 419 (30. 07. 1942, Dortmund -> Theresienstadt

Transport Ct, no. 263 (29. 01. 1943, Terezín -> Auschwitz

Murdered

Lucie was Herta’s older sister by seven years. She was killed in Auschwitz on 29th January 1943, aged 44.

And suddenly the trite wishes of love and hopes for a beautiful future were no longer trite. They had real meaning; the future was not going to be as they all dreamed of. The formula for signing off many of the poems (“zur Erinnerung von…”) as a wish to be remembered was very real – these sentimental poems were maybe the only thing Herta, if she had survived, had to remember her friends by and the good times in the 1920s. Here was a document, written by hand and directly expressing the personality of a murdered victim, maybe many victims, who so often appear just as a catalogue number. I follow AuschwitzMuseum, which posts daily photos of victims. Many appear as headshots in striped camp clothes with shaved heads - deliberately depersonalised and their history and life context erased. Others are photos from their life before the camps, with men and women dressed in elegant clothes. Those who had photos would have been middle-class. They too are of course poignant, but a photo, even where a gaze looks out at you, is a passive capturing of an image. And they are generally individuals which doesn’t give a sense of community; whereas handwriting is an active expression of that person to another, and there is something that speaks to us strongly through both the words and the curve of the letters.

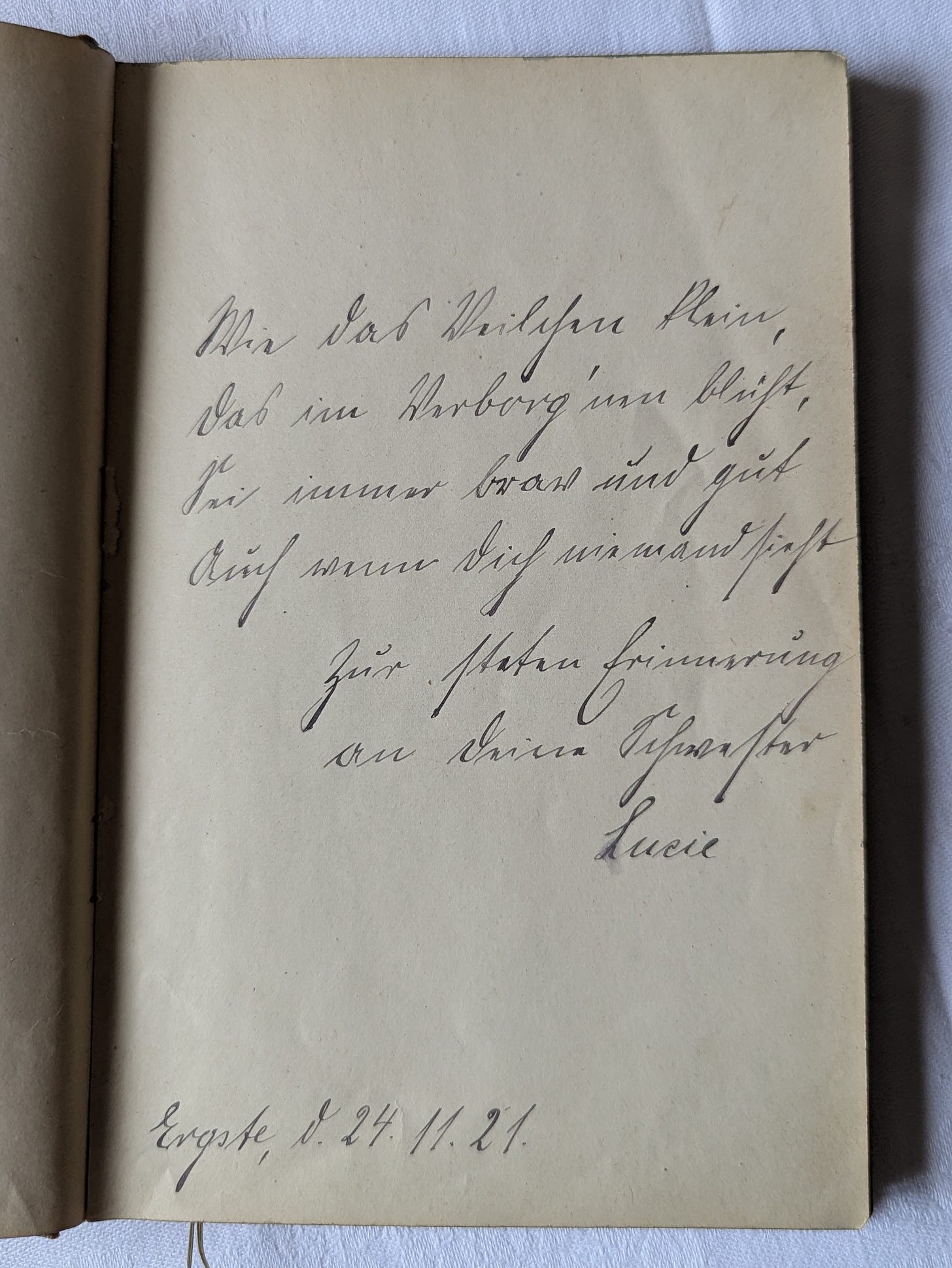

Lucie wrote the first poem in the book on 24th November 1921. It says

Wie das Veilchen klein

das im Verborg’nen blüht

Sei immer brav und gut

auch wenn dich niemand sieht.

zur steten Erinnerung an deiner Schwester Lucie

Like a violet small

that blooms in the hidden place

be always well-behaved and good

even when no one sees.

as a constant memory of your sister Lucie

These words must later have themselves been like hidden violets, beautiful, personal, treasured, and known only to Herta.

The young Herta went on to fill the book with dedications from her family and friends through 1922 and 1923 and there is a last entry in 1933. In total there are forty-four entries. Herta clearly had a lot of love for this little book and quite a wide circle of friends. I can’t delve into every person in it here now, and of course, many organisations and individuals have documented Holocaust victims in great detail.2 This is not historical research providing new information, but I’ve dipped in, and dug around just a bit (actually more than a bit), and it was surprisingly easy to find online references. My aim here is to bring the future historical context to bear on these words of a family and friendship circle, written by hand in this personally-treasured book, before the shadows descended.

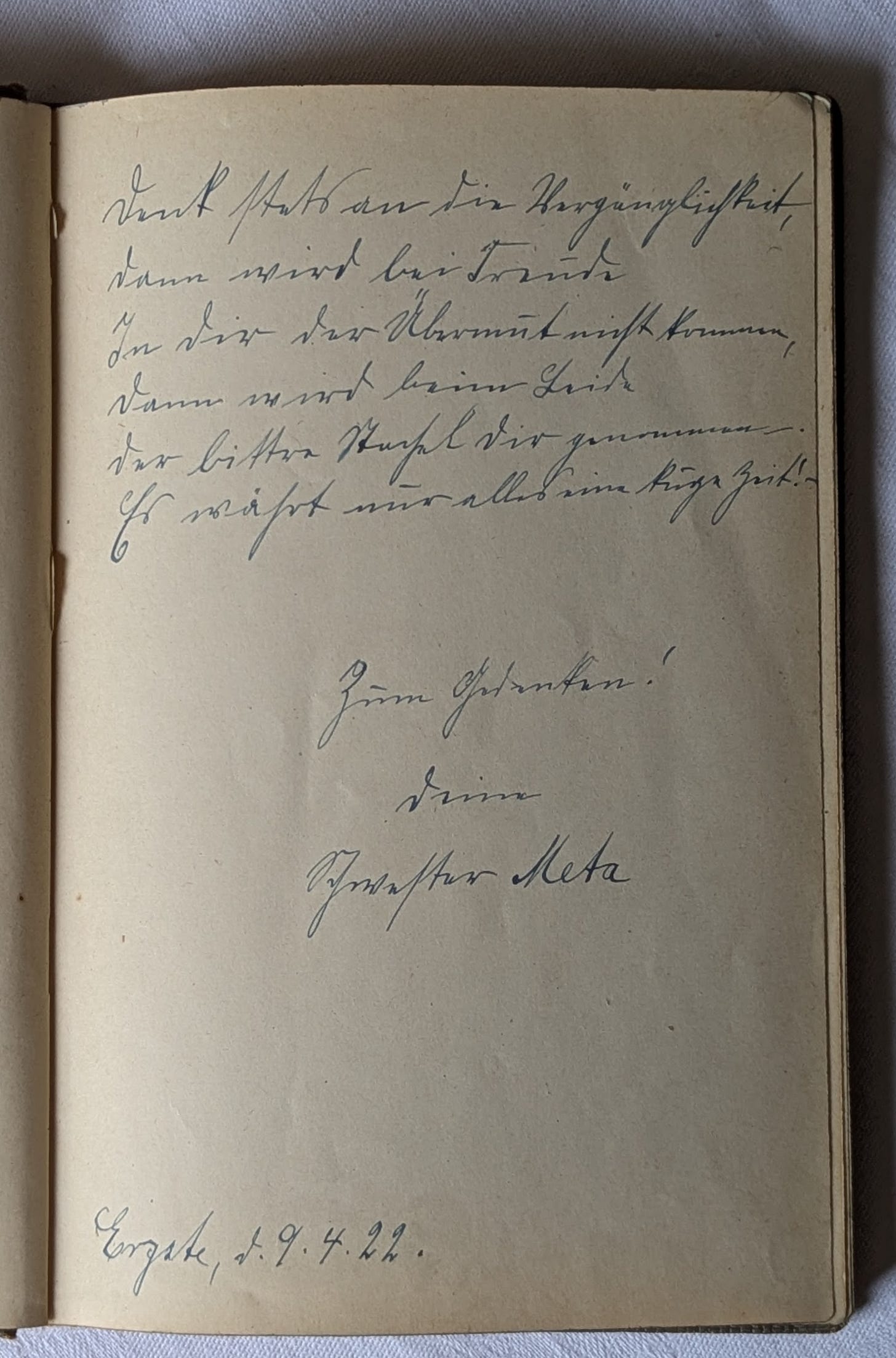

Oldest sister Meta was also a Holocaust victim.

Born 05. 10. 1887

Last residence before deportation: Ergste

Transport X/1, no. 418 (30. 07. 1942, Dortmund -> Terezín)

Transport Ct, no. 262 (29. 01. 1943, Terezín -> Auschwitz)

Murdered

29 January 1943. The two sisters travelled together on that train to Auschwitz. I wonder if they were able to be together in those over-crowded cattle trucks. Had they been able to be a support to each other through those terrible 6 months? The records show that on that one train were 1000 people. 988 were murdered. 12 survived.

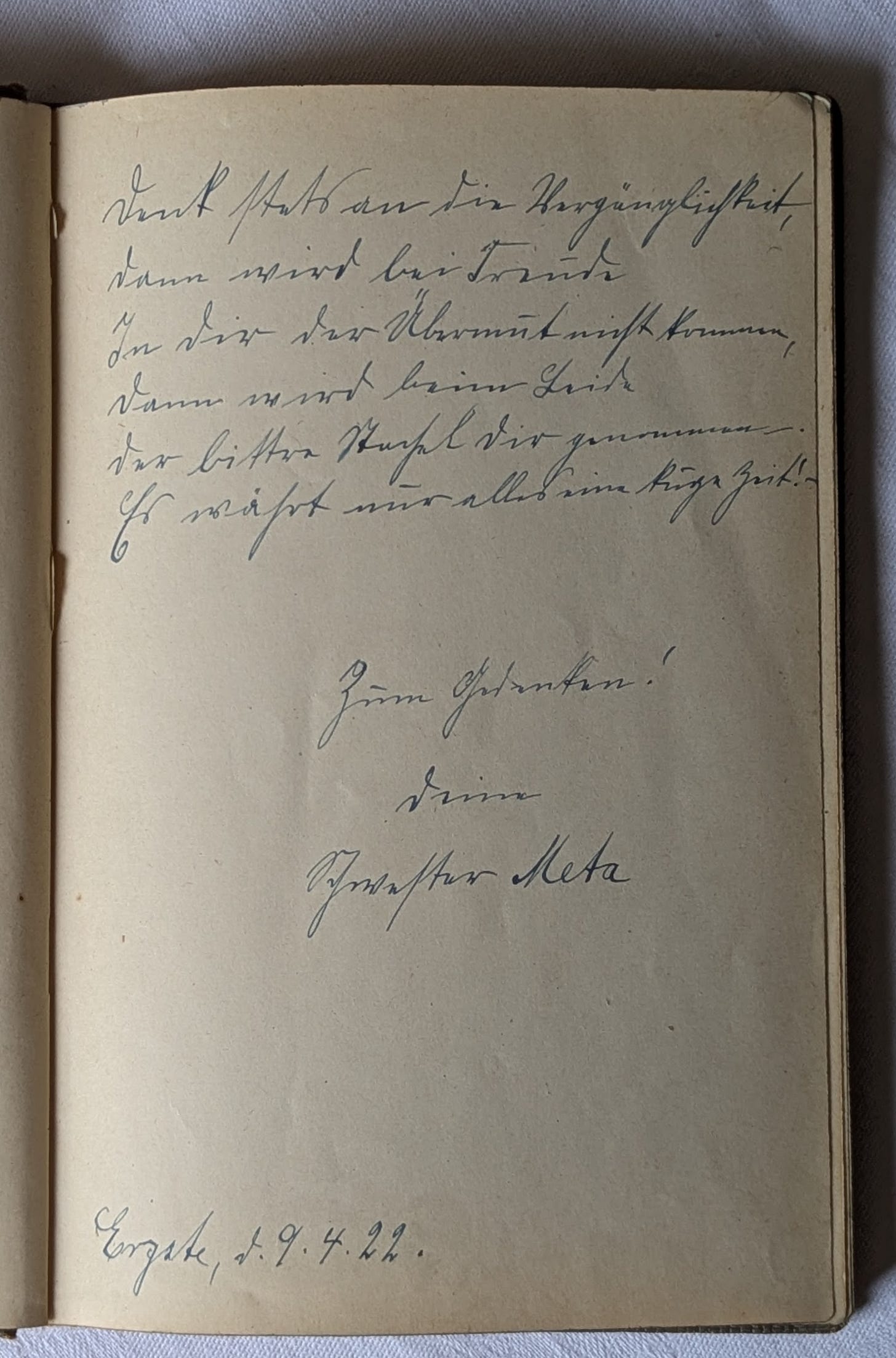

Meta wrote her dedication in the poesie album on 9 April 1922. For now I can only make out the first line properly. The rest is poignant too, speaking I think of suffering and a bitter school, lasting just a short time. Will come back to it later.

Denk stets and die Vergänglichkeit..

Always remember the passing nature of things…

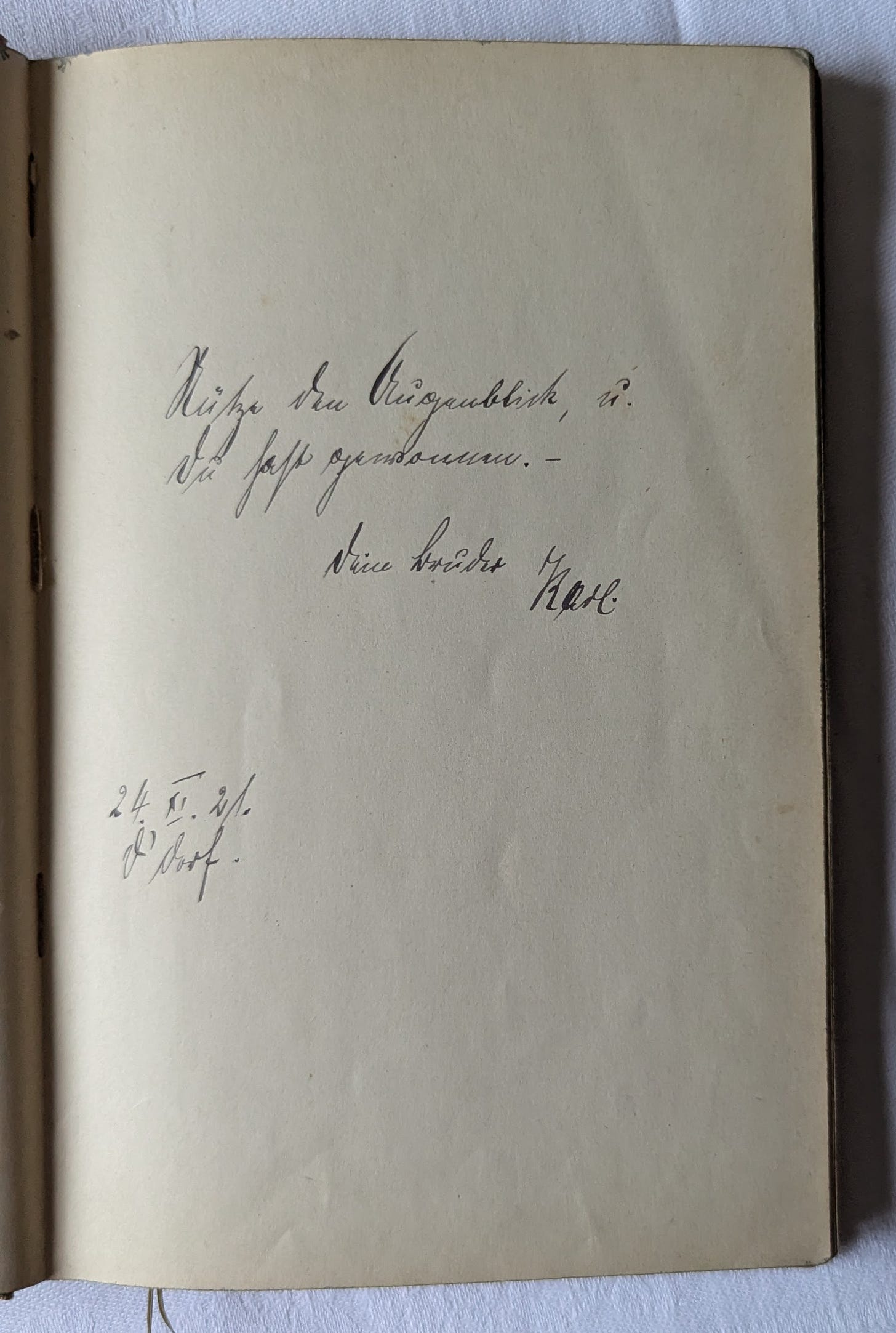

On the previous page, brother Karl, born 1902, has a short entry in the book, written 24.11.1921:

Nutze den Augenblick und Du hast gewonnen.

Dein Bruder Karl

Seize the moment and you’re a winner.

Your brother Karl

1921

He was also murdered. Born on the 27 August 1902 in Ergste/Iserlohn/Westfalen residing in Berlin (Wilmersdorf). Deportation from Berlin 3 March 1943, to Auschwitz.

He'd moved to the big city Berlin at some point, maybe a young urban professional of his time. Rounded up in a different city, he probably won’t have known that his two sisters had been taken to Auschwitz a couple of months before him.

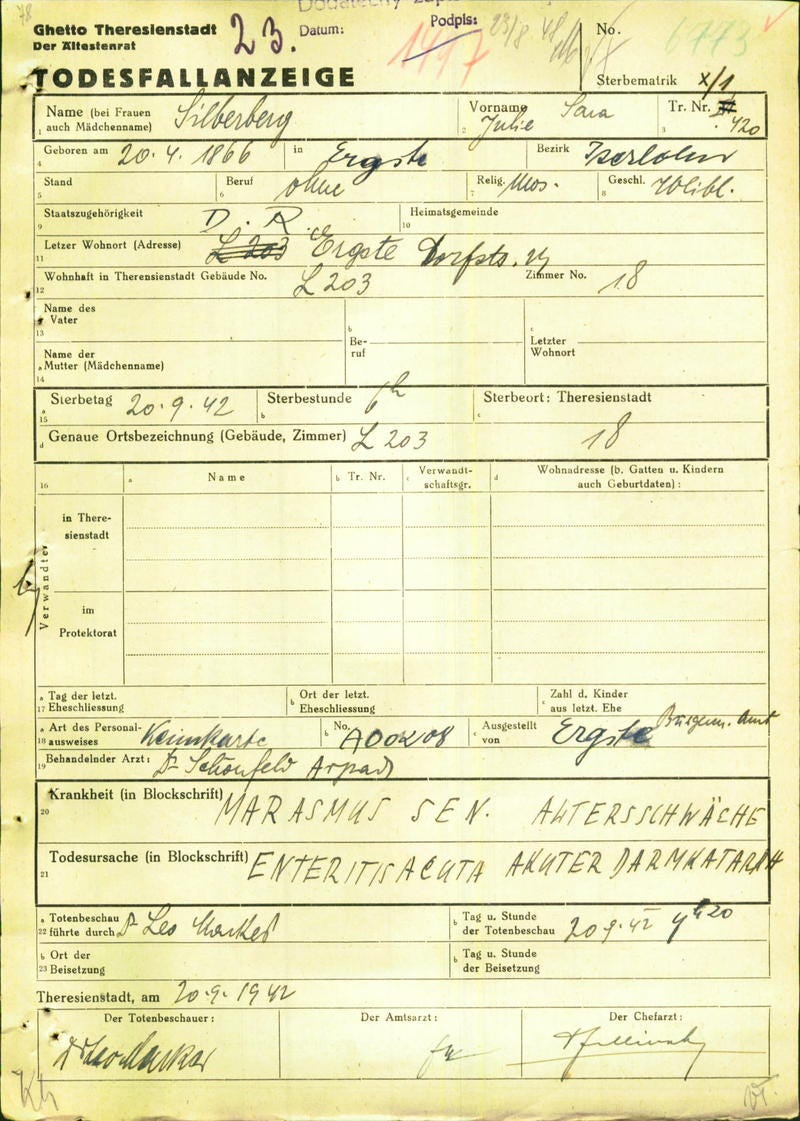

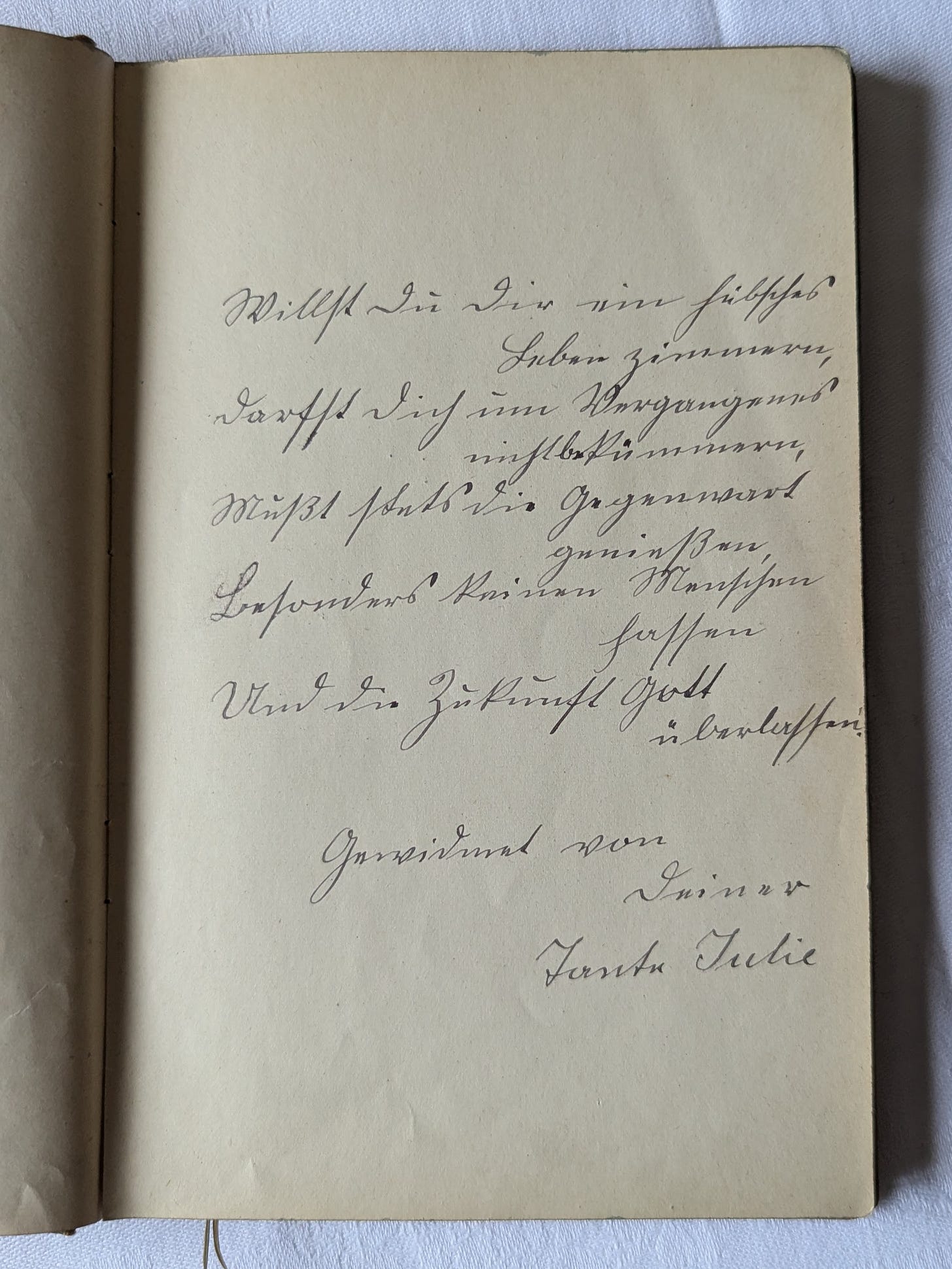

And then there is Meta, Lucie, Karl and Herta’s Aunt Julie Silberberg. Theirs are the first entries in the book. Naturally; they were family, apparently close, and lived in the same place.

Born 20. 04. 1866

Last residence before deportation: Ergste

Transport X/1, no. 420 (30. 07. 1942, Dortmund -> Terezín)

Murdered 20. 09. 1942 Terezín

Aunt Julie was apparently deaf-mute.3 She wasn’t taken to Auschwitz. She only survived two months in Theresienstadt. Here is her death certificate, from public camp records. She is said to die of “Marasmus Altersschwäche” - malnutrition, old age. Still ‘murder’ in the Holocaust record, of course. She was born in 1866, in a completely different world, and was 76 when she died.

This was what Aunt Julie wrote in 1922:

Willst Du Dir ein hübsches Leben zimmern

Darfst Dich nicht um Vergangenheit nicht bekümmern

Musst stets die Gegenwart geniessen

Besonders keinen Menschen hassen

Und die Zukunft Gott überlassen

Gewidmet Deiner Tante Julie

If you want to live a pretty life

You mustn’t worry yourself about the past

Always enjoy the present

Especially don’t hate any person

And leave the future to God.

Dedicated by your Aunt Julie

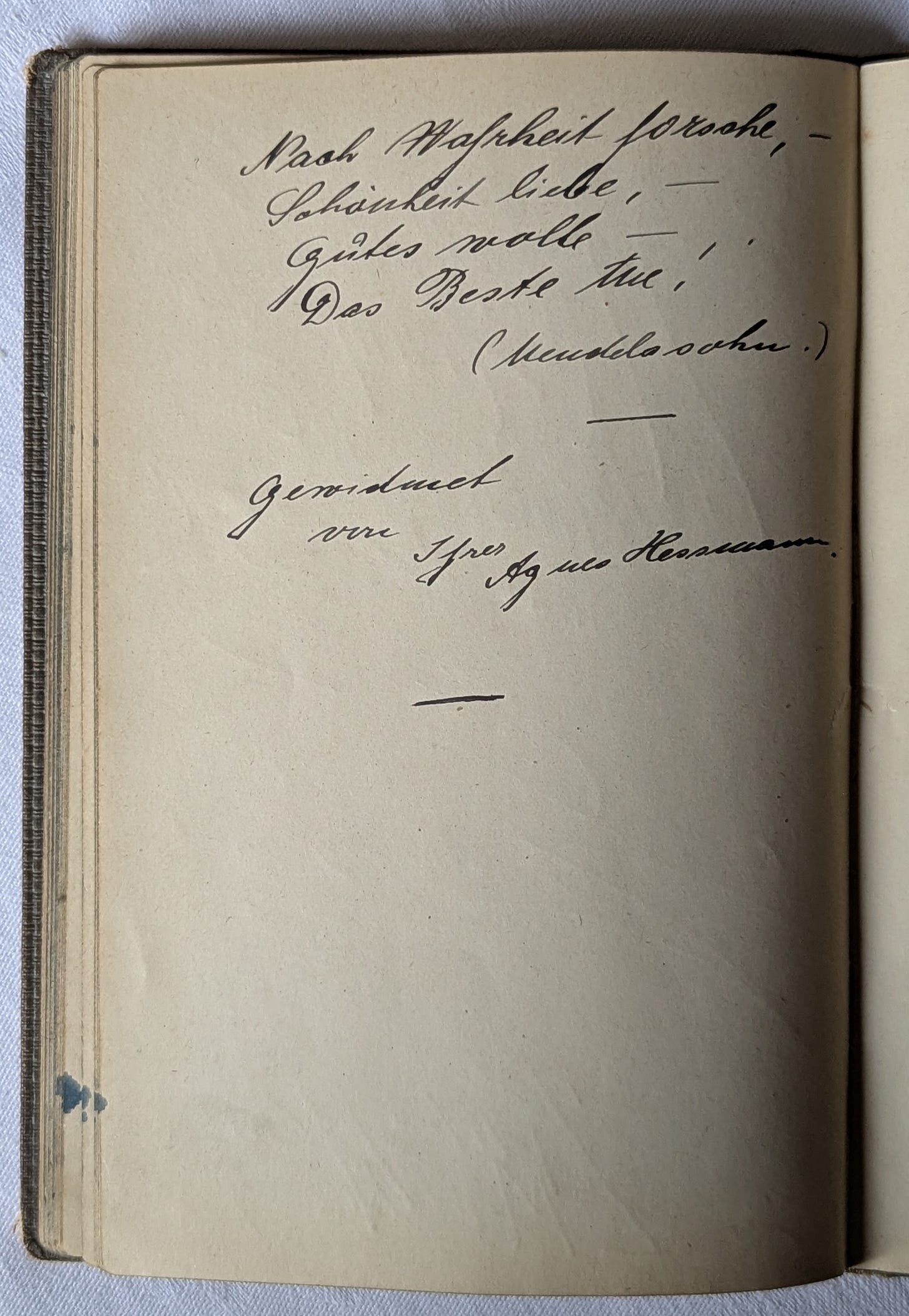

To say that’s bitter-sweet is an understatement. What amazing people, and powerful, positive sentiments. Simple common sense and values as you may find in the top self-help bestsellers of today. Enjoy the present. Seize the moment. Remember things are fleeting. Don’t hate any person.

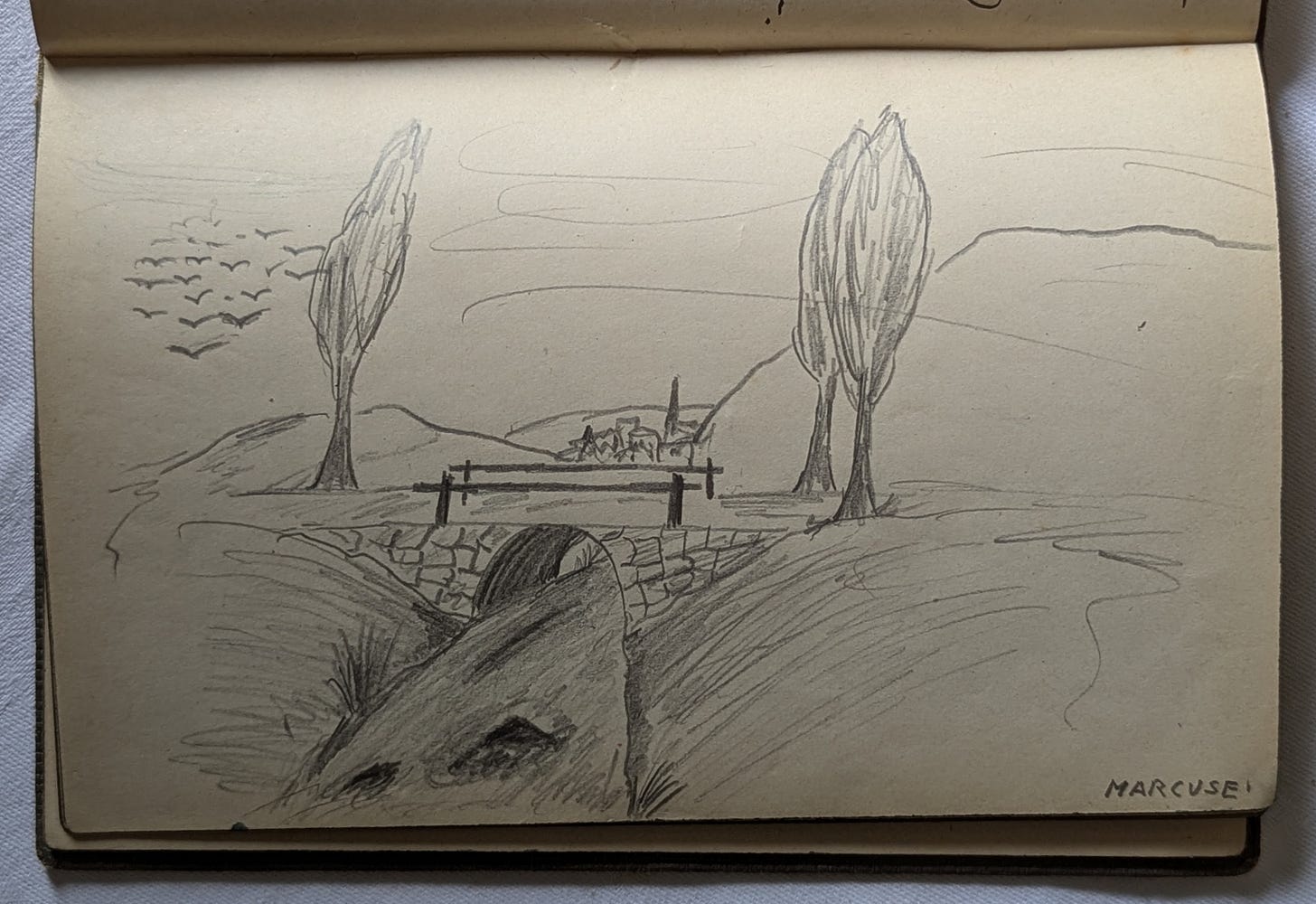

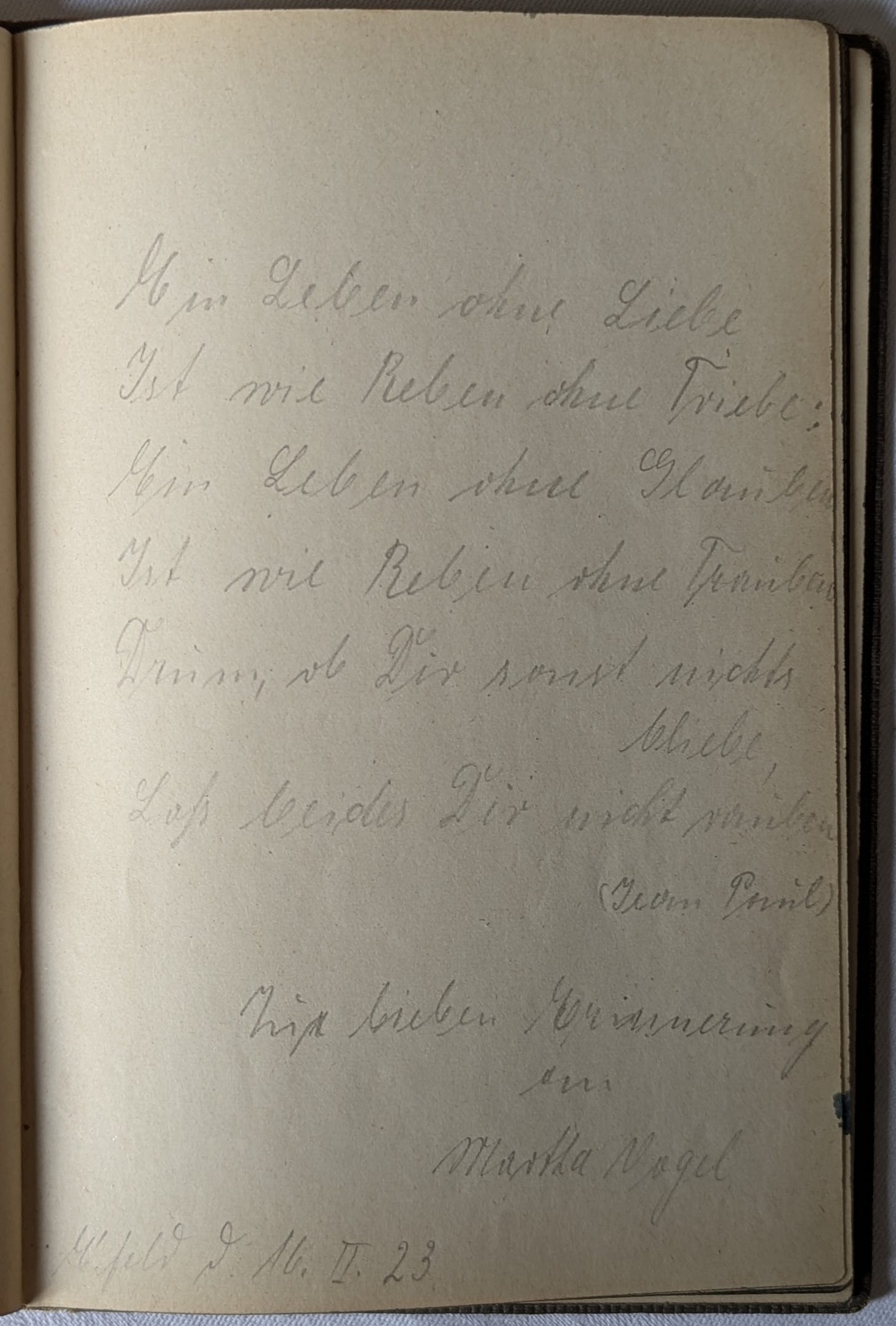

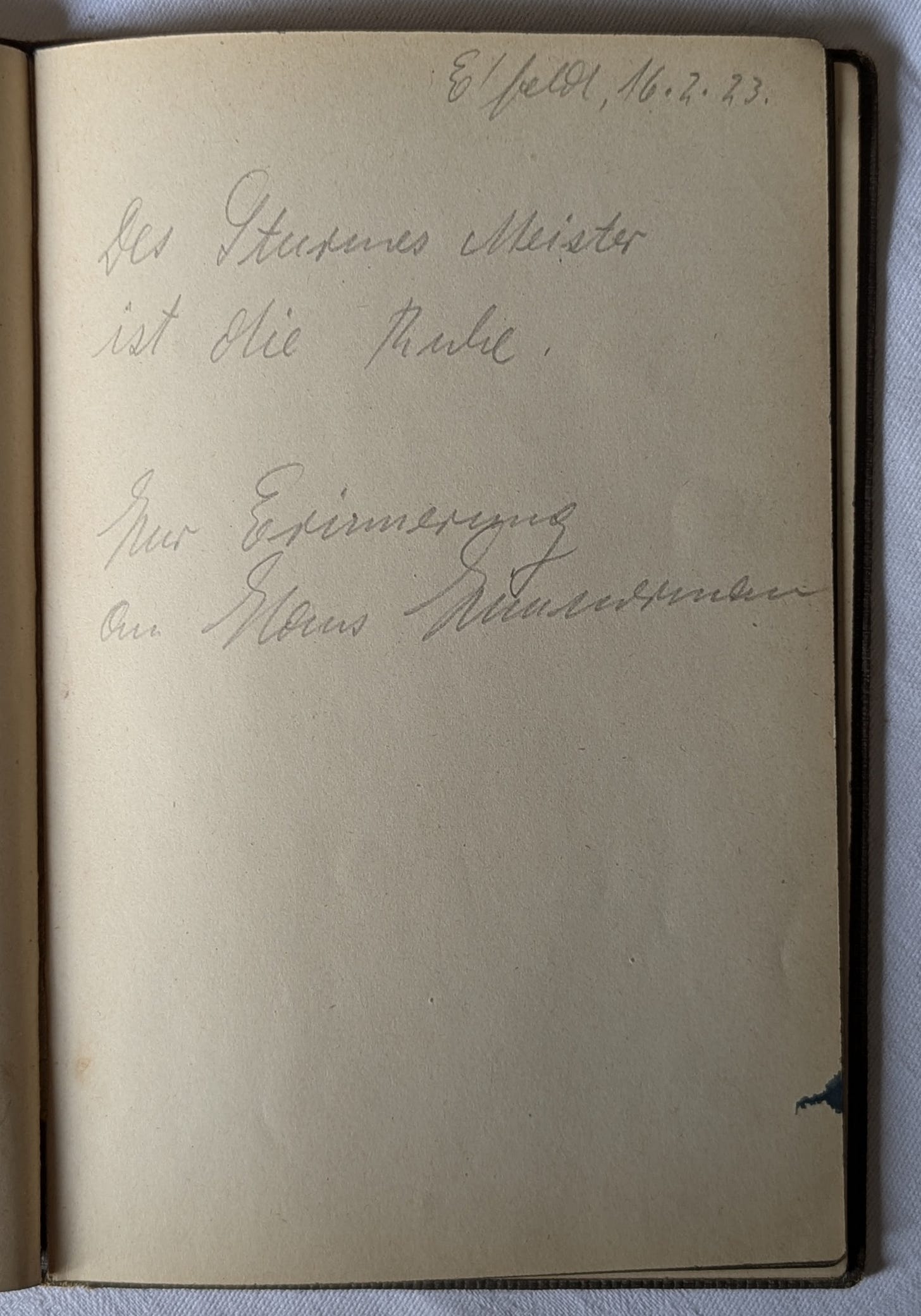

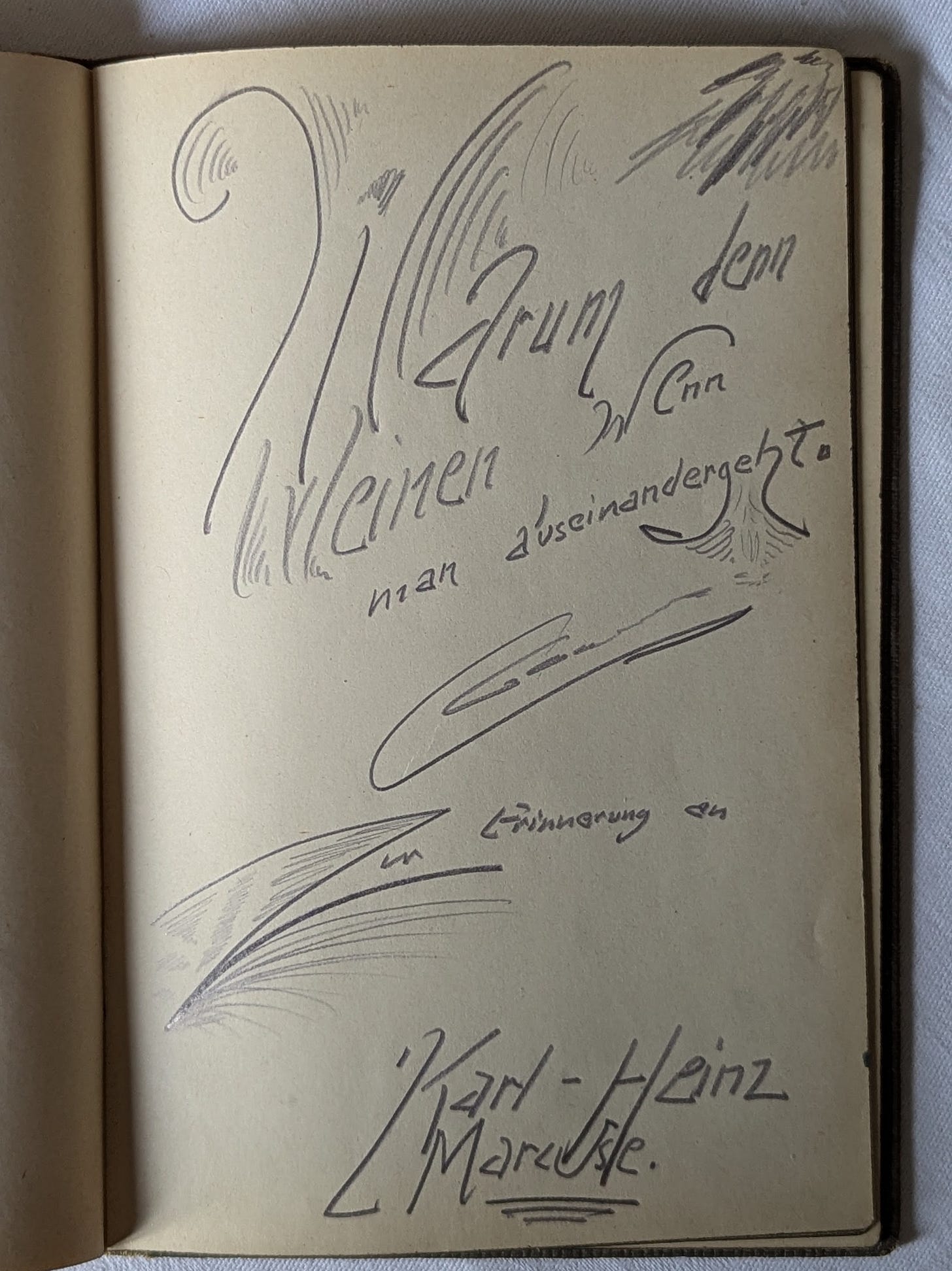

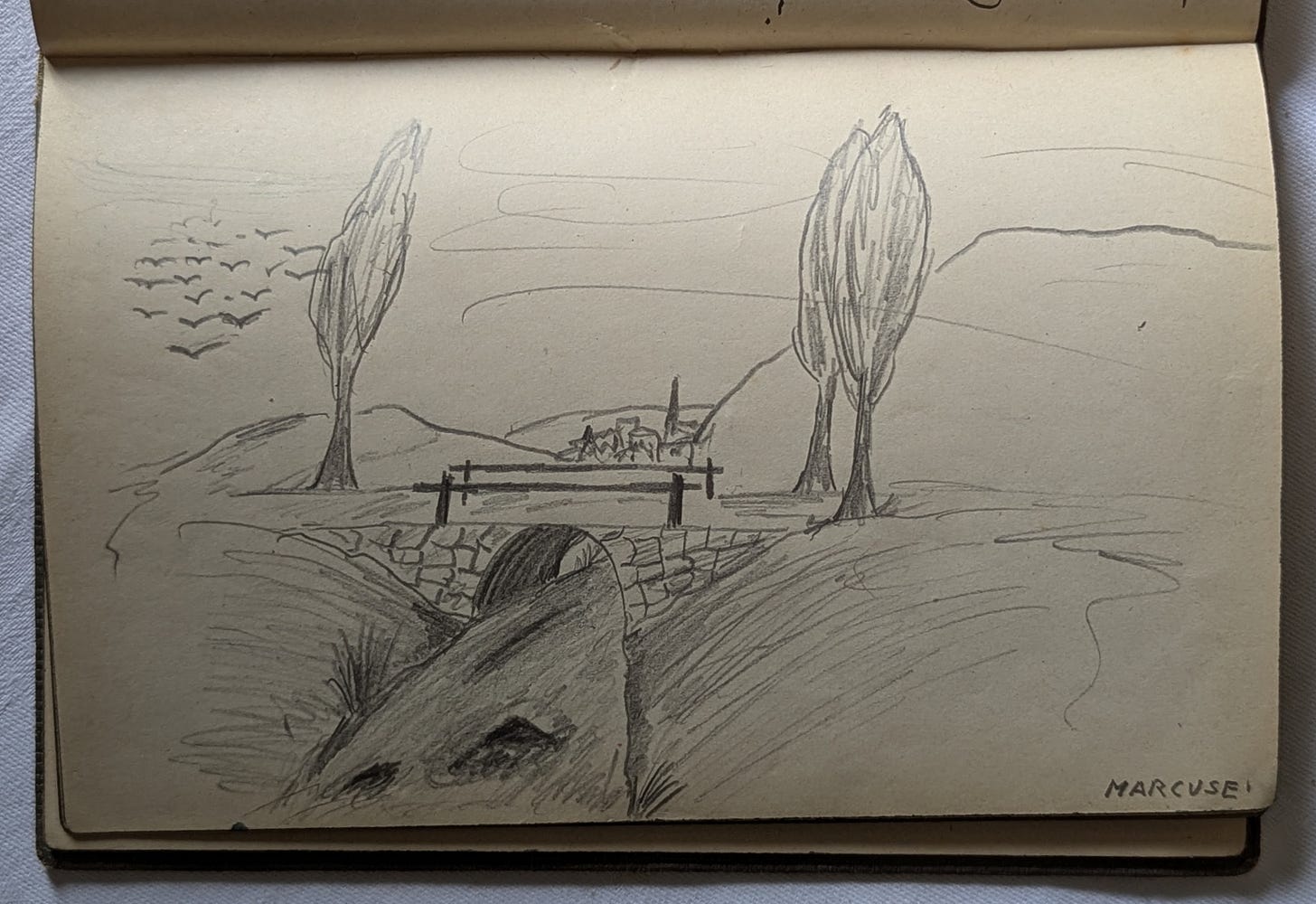

Herta was clearly a popular girl with a wide, educated social circle who all had exquisite handwriting and ability to write poems, or at least trot them out from memory. She seems to have been very much a young German girl first, with an incidental Jewish background as this doesn’t seem to be referenced in these pages. The names are not all Jewish sounding, but I’m not an expert. So when I searched the rather German-sounding Karl-Heinz Marcuse and found that he too, born 19 January 1907, appears on a Holocaust database as someone who had had his citizenship revoked as he was Jewish; he survived and eventually made it to Switzerland. The Karl-Heinz Marcuse in this record I found was born in Halle further east, but the dates fit with the pictures he drew in Herta’s book. If he was born in 1907, he’d have been 16 in 1923. His dedications would be exactly what a 16-year old would write, so I assume it is the same Karl-Heinz and that his family had moved west.

He took three pages, writing from Elberfeld, Wuppertal, 50km to the south-west of Ergste.

Verzehrened sind die Feuer der Liebe;

Aber auf den Trümmern wächst die Gute

The fires of love tear apart:

But on the ruins grows goodness.

To remember Karl-Heinz Marcuse

Elberfeld 6.2.23

Warum denn weinen wenn man auseinandergeht?

Why cry when you are separated?

And he drew a little country scene. Herta was just over 2 years older than Karl-Heinz. Maybe they’d had a first teenage first romance together. In his first picture above, that looks like a little cross of hope arising from the ashes of fire, and at the centre of the village is a church spire. Maybe they were even rather christianised Jews.

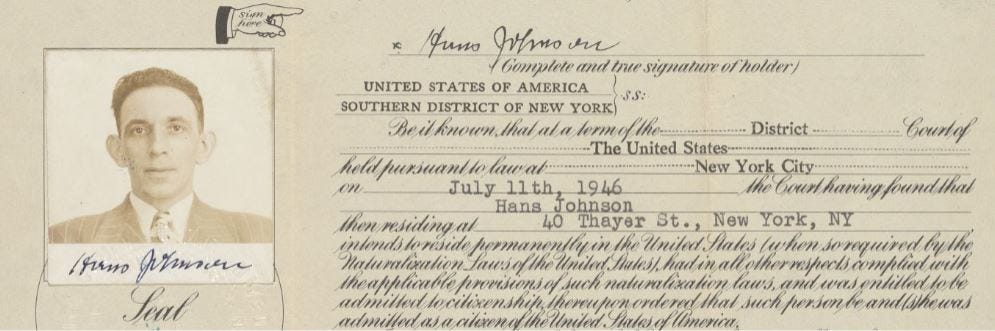

Ericka Jonassohn, another friend who wrote in the book is a more Jewish name. I eventually found that Ericka survived by fleeing to England and then to the USA with her brothers Herbert and Hans, though her mother Frieda died on 5 July 1942 in Theresienstadt, aged 72.4

This is Ericka’s page

Immer heiter

gott hilft weiter!

Always be cheerful

god will help with the rest!

I found records of a Hans Jonassohn (Hans Johnson) born in Ergste, Germany in 1906. This seems to be Ericka’s brother. He married Betty (Betti) Levi, born in Katzenfurth in 1908. Their daughter Lora (Karolina) was born in 1933 in Köln. Hans fled Germany for Mexico and ended up in Cuba. Six months later his wife and daughter followed. They reached the United States in December 1940. There is a collection of Hans Johnson’s family papers here in the US Holocaust Memorial Museum. If that is the same Hans, then this is a picture of Ericka’s brother here, in 1946, when the war was over but the full horrors of the Holocaust were known, from his US naturalisation certificate.

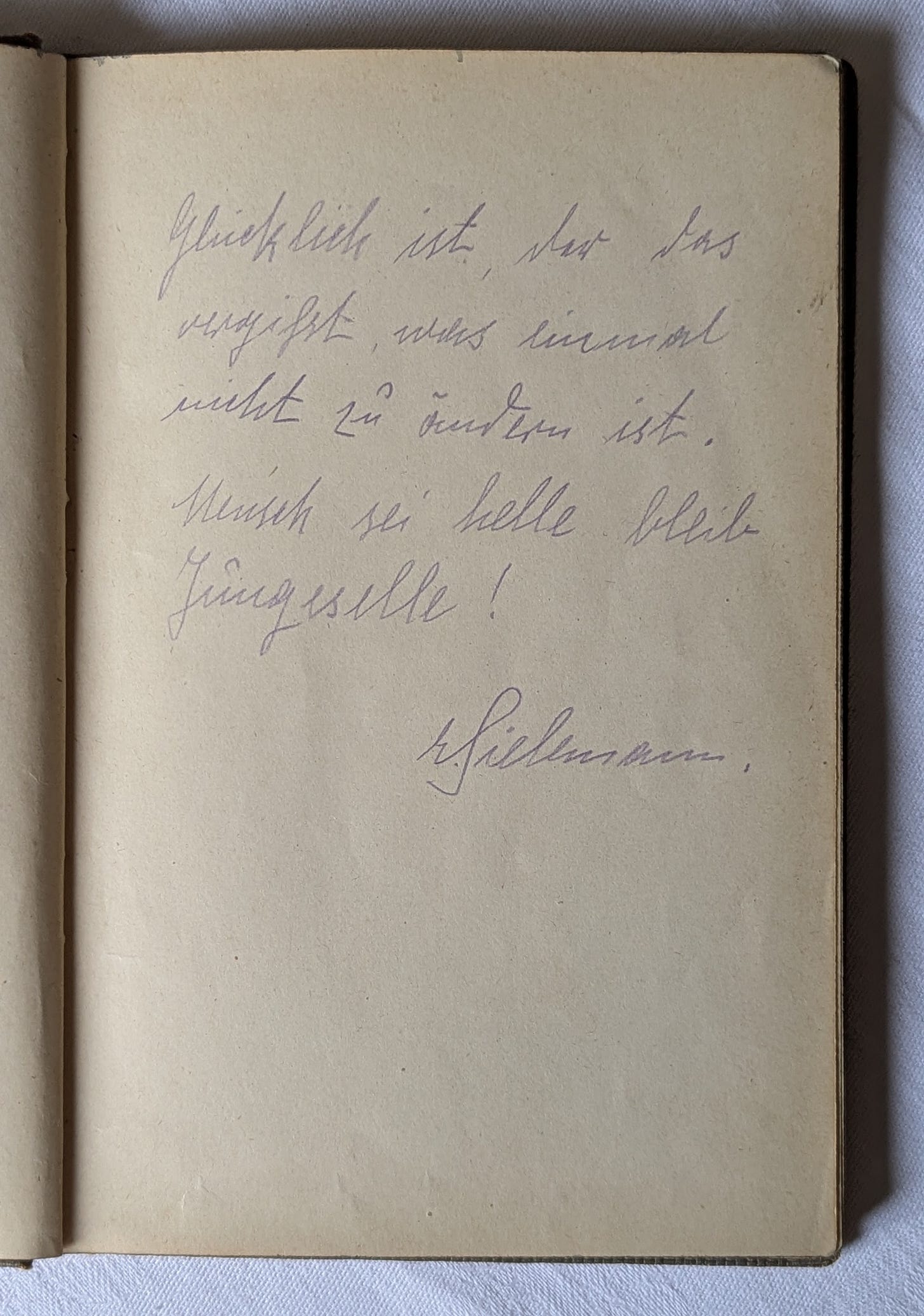

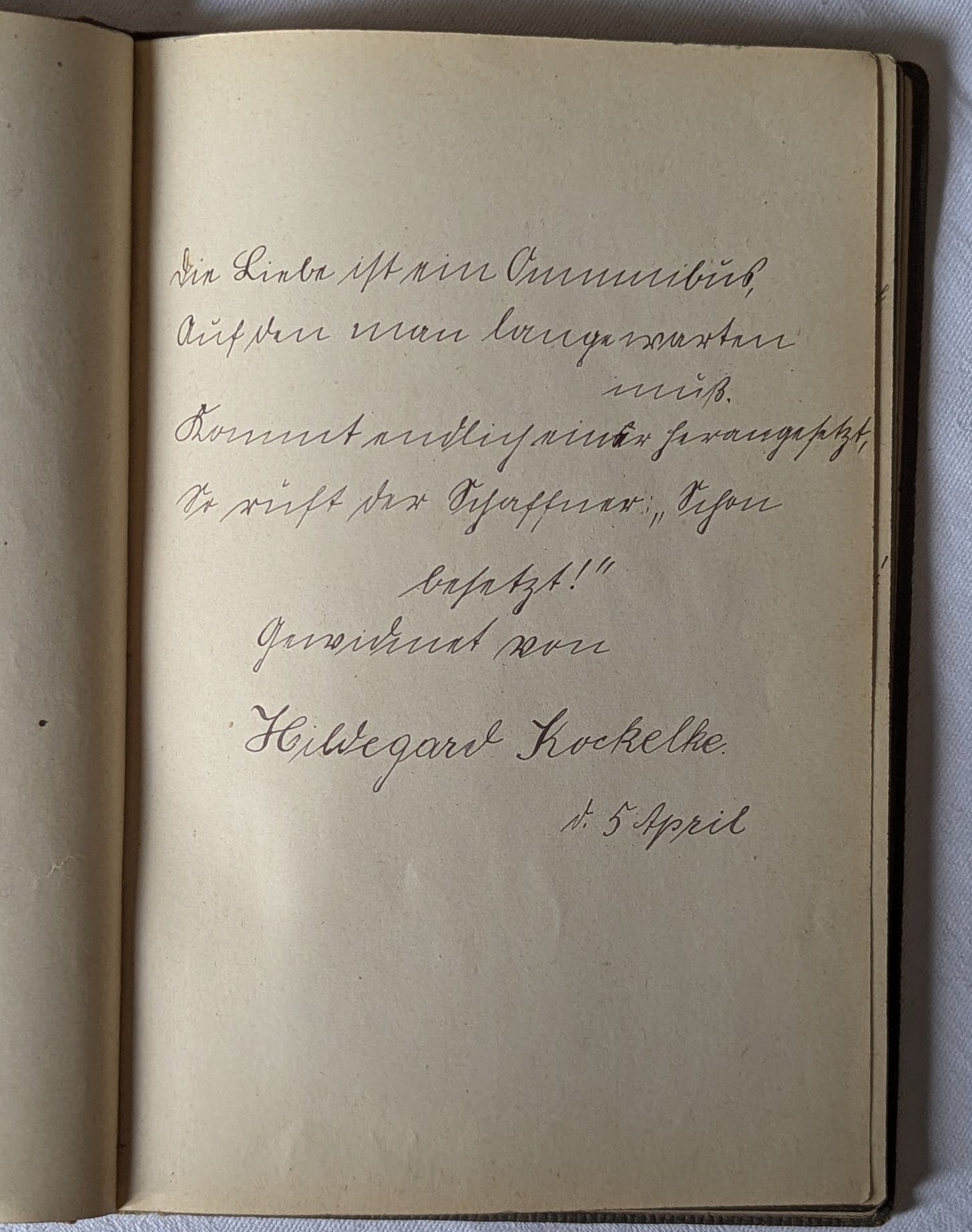

Hildegarde Kockelke seems to have been one of Herta’s non-Jewish friends. I found what seems to be her grave. She married and lived until 1971.

Her poem on 5 April 1922 is a little more playful that the others. And maybe refers to a romantic breakup Herta was going through. Here’s my mum reading it. The translation is

Love is an omnibus

That you have to wait so long for

When finally one shows up

The conductor calls out “already full”!

dedicated by

Hildegarde Kockelke

5 April

But what happened to Herta? She didn’t appear in the records of Holocaust victims; instead, I found her on a list of people who had claimed reparations for their loss. She came to London in 1935. Maybe she came with her friend Ericka. She changed her name to Herta Silver. And that’s how the book would have ended up with my mother - who was very emotionally touched when I told her that the book was from a Jewish German family, she hadn’t known. She then remembered that she had been given the book by an older German Jewish lady. That wouldn’t, I think, have been Herta herself but maybe someone close to her. It seems that Herta had brought the book with her to England in 1935 as one of her treasured possessions. And now it stands as a testament to a family who were killed, and a network of relations and friendships that were torn apart by history.

Another search revealed that the family have Stolperstein dedications in the town of Ergste. The translation of this German word is ‘stumbling stone’. They are small plaques placed on the ground to memorialise victims of the Holocaust. Though I’ve never seen one, as you walk through an ordinary town you may ‘stumble’ across them and pause for a moment.

Karl is not among them as he’d moved away to Berlin. Although she survived, Herta is included with her anglicised name. Her Stolperstein says “Flucht”, Flight 1935 England. So she did flee. How amazing to have uncovered a little book that brings these four little brass plaques alive.

The town of Schwerte, of which Ergste is a part, has a total of 63 Stolpersteine that you can see detailed here. Each with their own equally human and hidden stories.

There are many questions. Apart from the actual experience: how were they rounded up, treated in Theresienstadt concentration camp, what was daily life like there, how was their state of mind? We can guess those things. Why had Herta left? Was it because of increasing pressures on Jews? In that case, why didn’t Lucie, Meta and Karl leave? How was life in Ergste through the 1920s? This little book was started just as Germany entered its first period of hyperinflation. In early 1922 one Dollar was 320 German Marks. In November 1923 you needed 4,210,500,000,000 Marks to buy one dollar!5 The thinking that nothing is permanent was very much present in the life of an ordinary German, which may explain the philosophical outlook in some of the poems as an attempt to retain some personal sanity. Did Herta have a job? Romance? And then what happened through the 1930s after Hitler took power? Where did all the forty writers in Herta’s book end up? How many were murdered? Killed in war? Who escaped and where to? Did any of the book’s contributors maybe even join the Nazi party? Who managed to keep in touch with each other?

The later tragedies destroyed the promises of youth. But the hopes of these young people at that time have endured by being written down and are renewed to us through these pages.

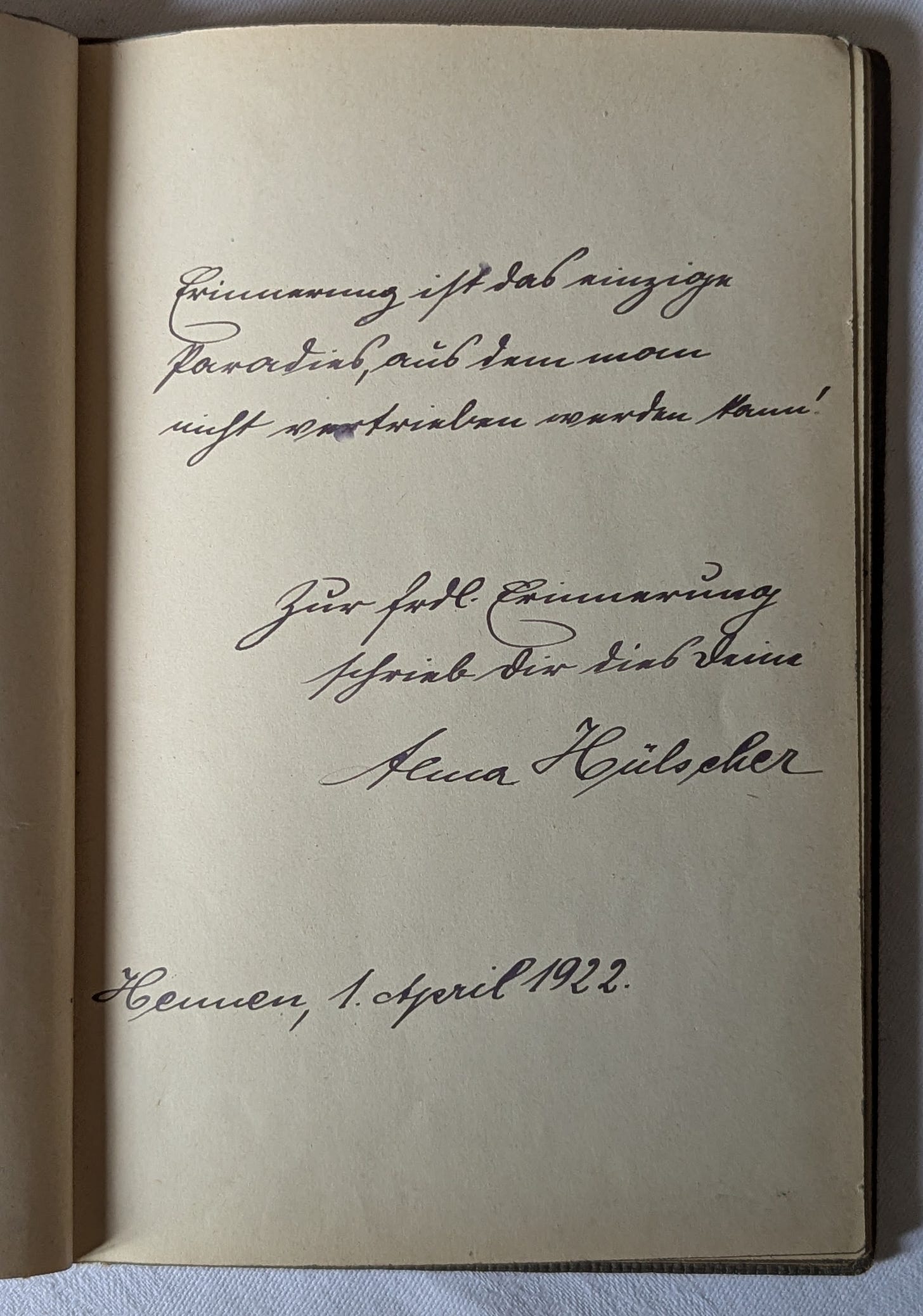

Here is Mum reading one of the other of the entries, which translates: “Memory is the only Paradise from which one cannot be driven out…”

The question is what to do next. Should we try to get the book back to Herta’s family, if we can find them? Or should it go to a local museum? Or to a specific Jewish or Holocaust memorial? No doubt I’ll keep digging and find the right thing.

Below (when I get a mo) I’m going to add the photos of the book in full, since no one else is going to and this is a pretty good platform on which to publish a record. The town of Ergste will have a little bit more of its history coloured in. And maybe one day some relatives of the people mentioned in this diary might find a name here and add to the story, or may remember their grandmother talking of so-and-so. Maybe, just as property that was stolen needs to be restored or compensated, the family friendships that were taken away from this group of young people from the 1920s might be restored amongst their descendants. That’s a long shot, I know but it’s all about connections, isn’t it.

For now, you are reading about it, you’ve connected, and that is important. Thank you.

****************************

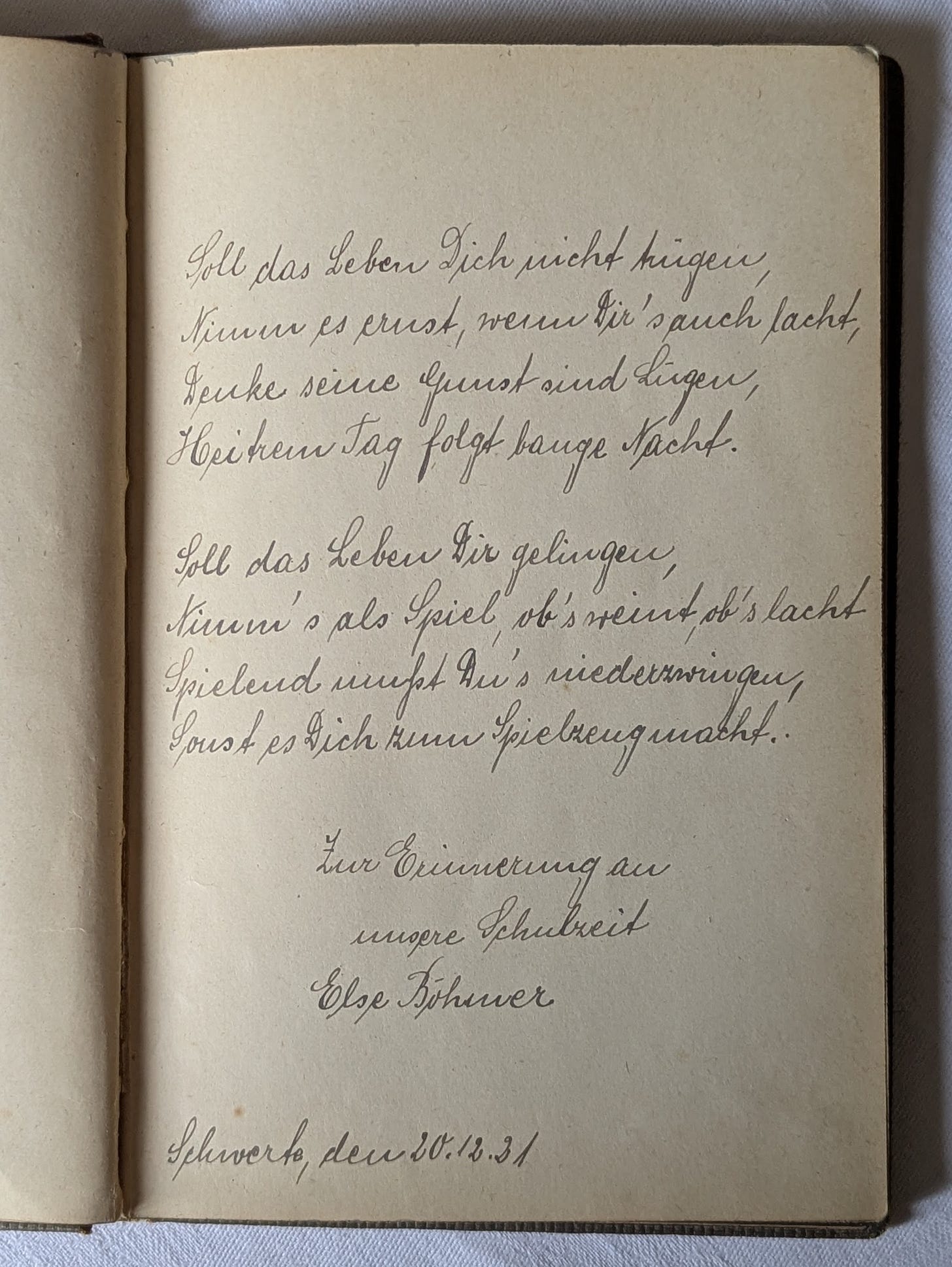

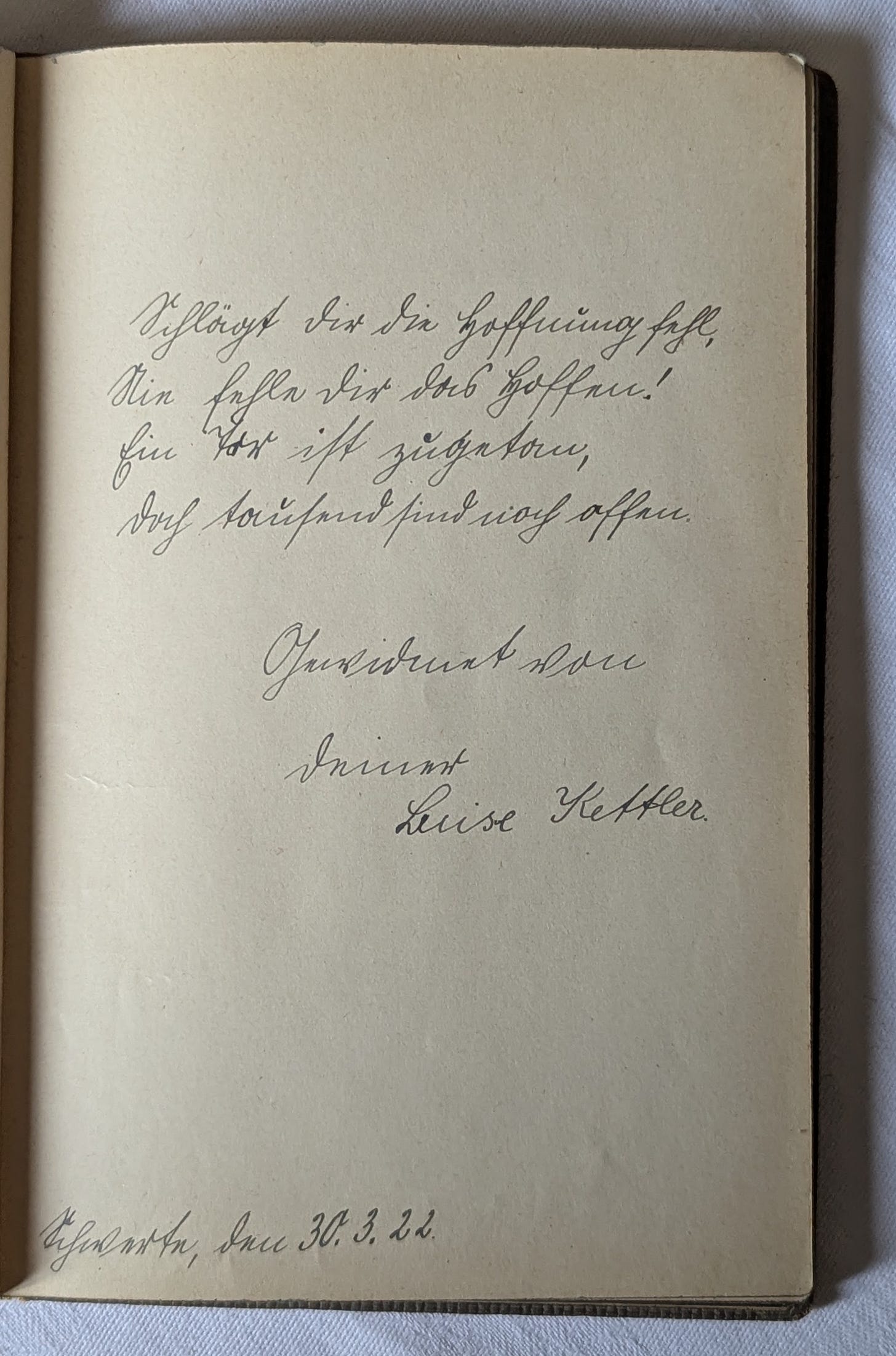

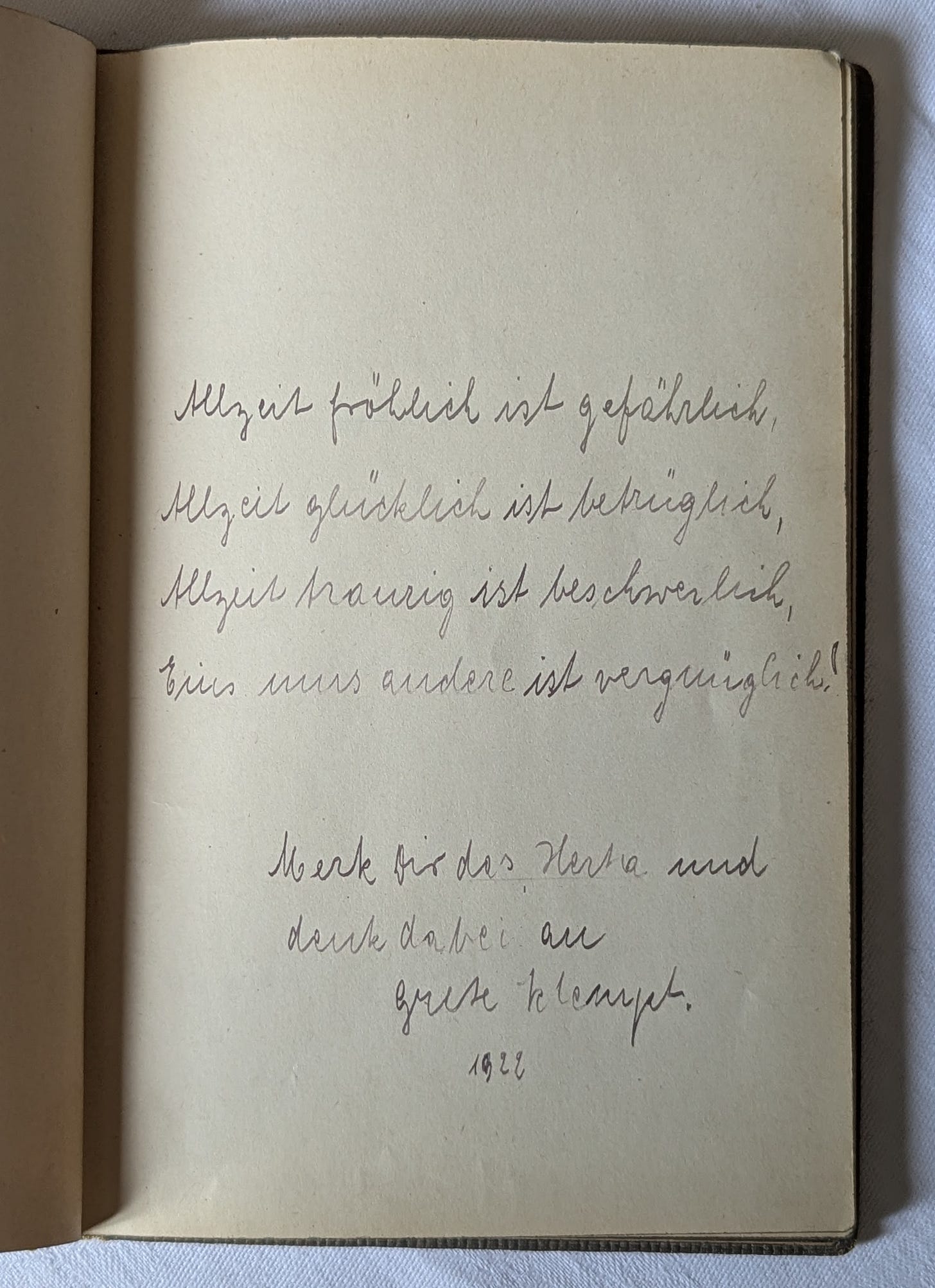

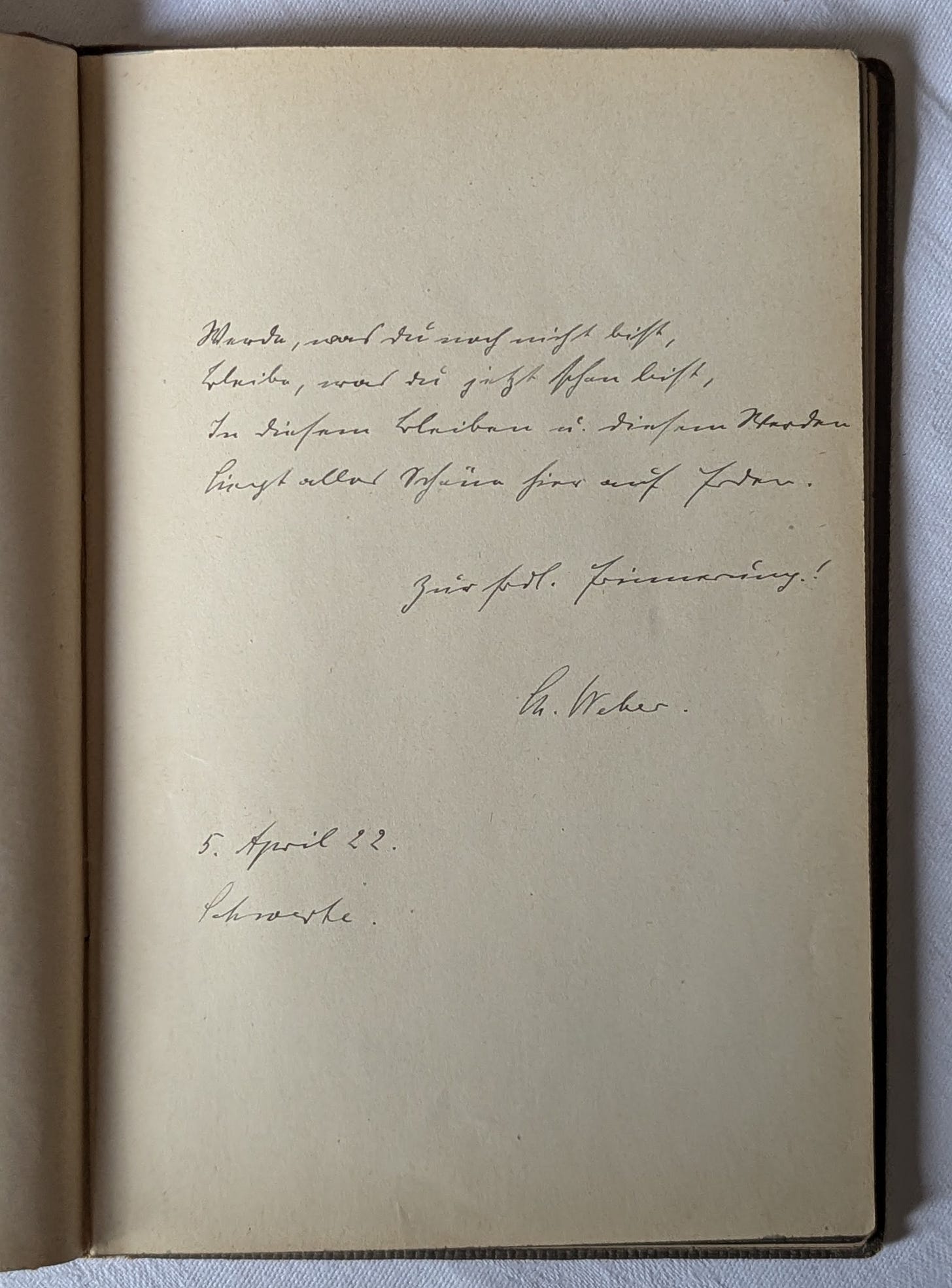

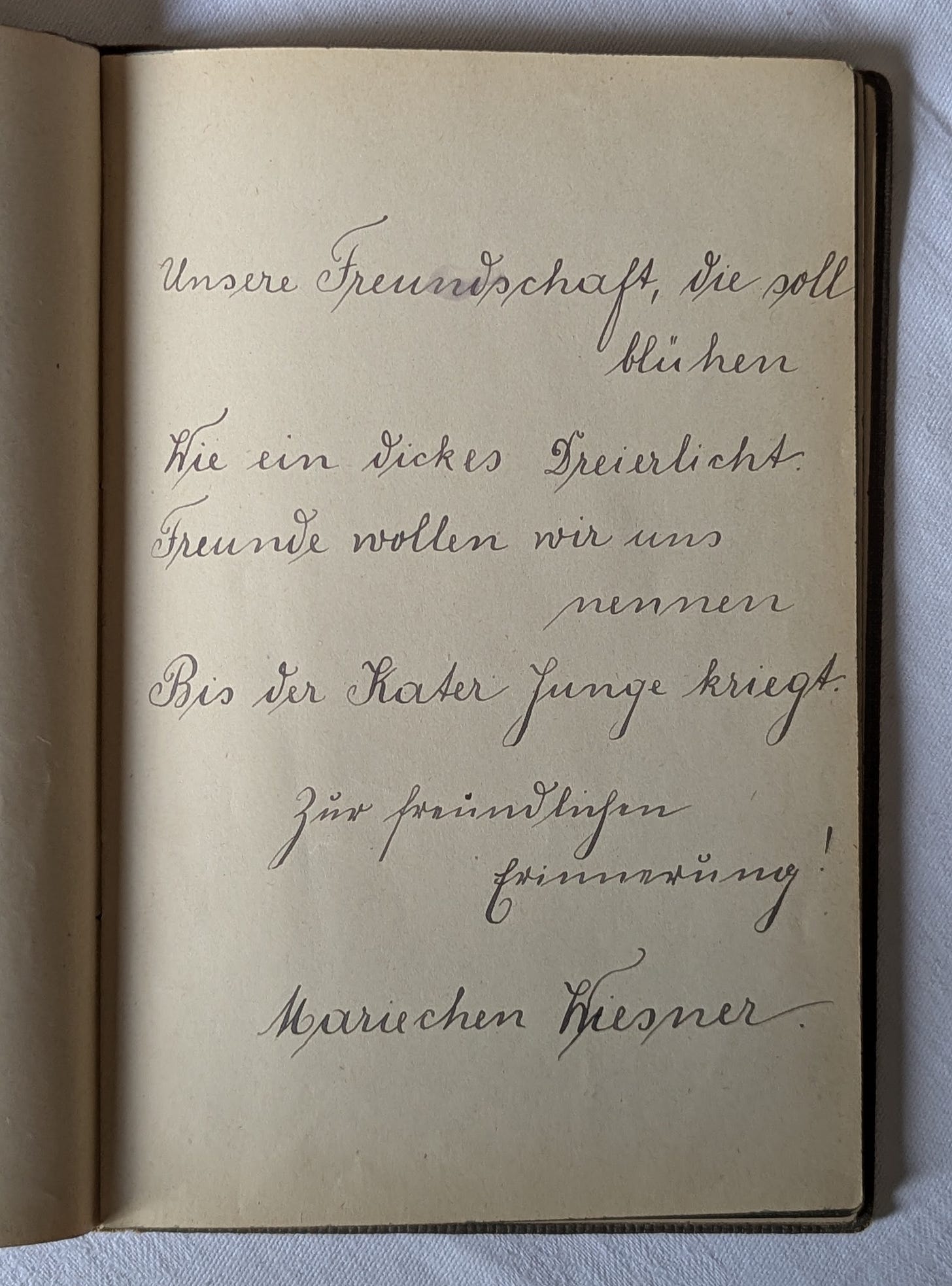

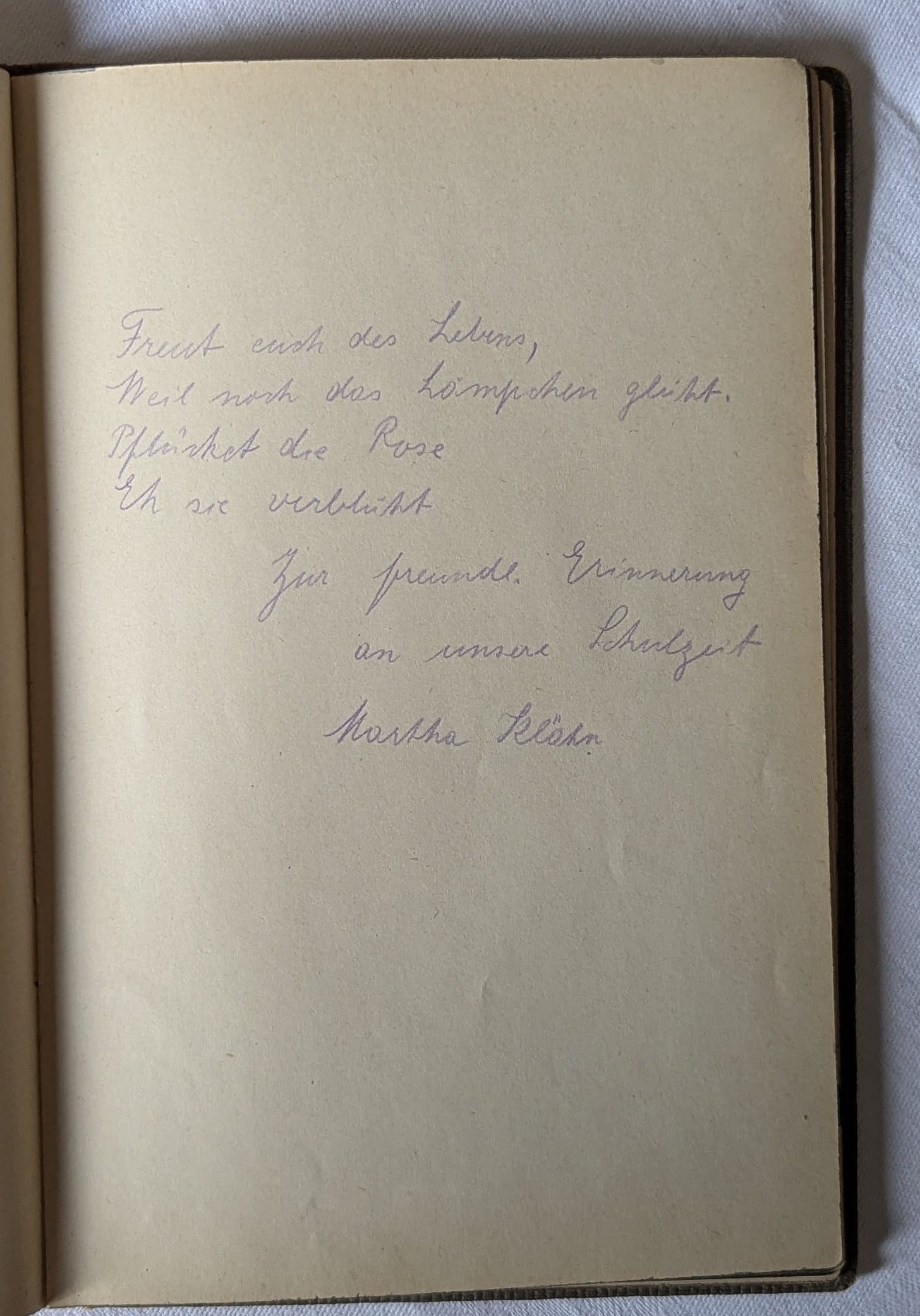

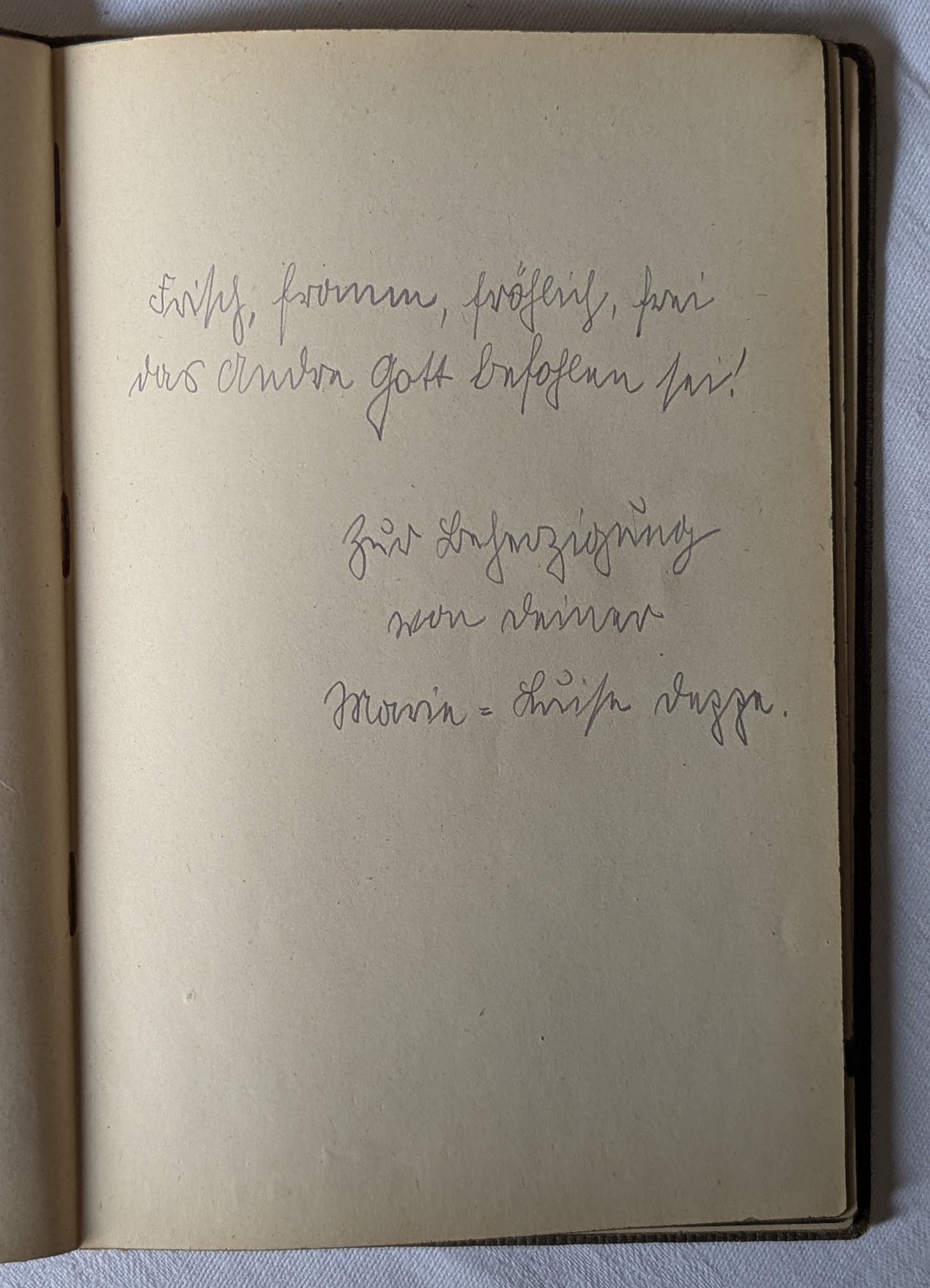

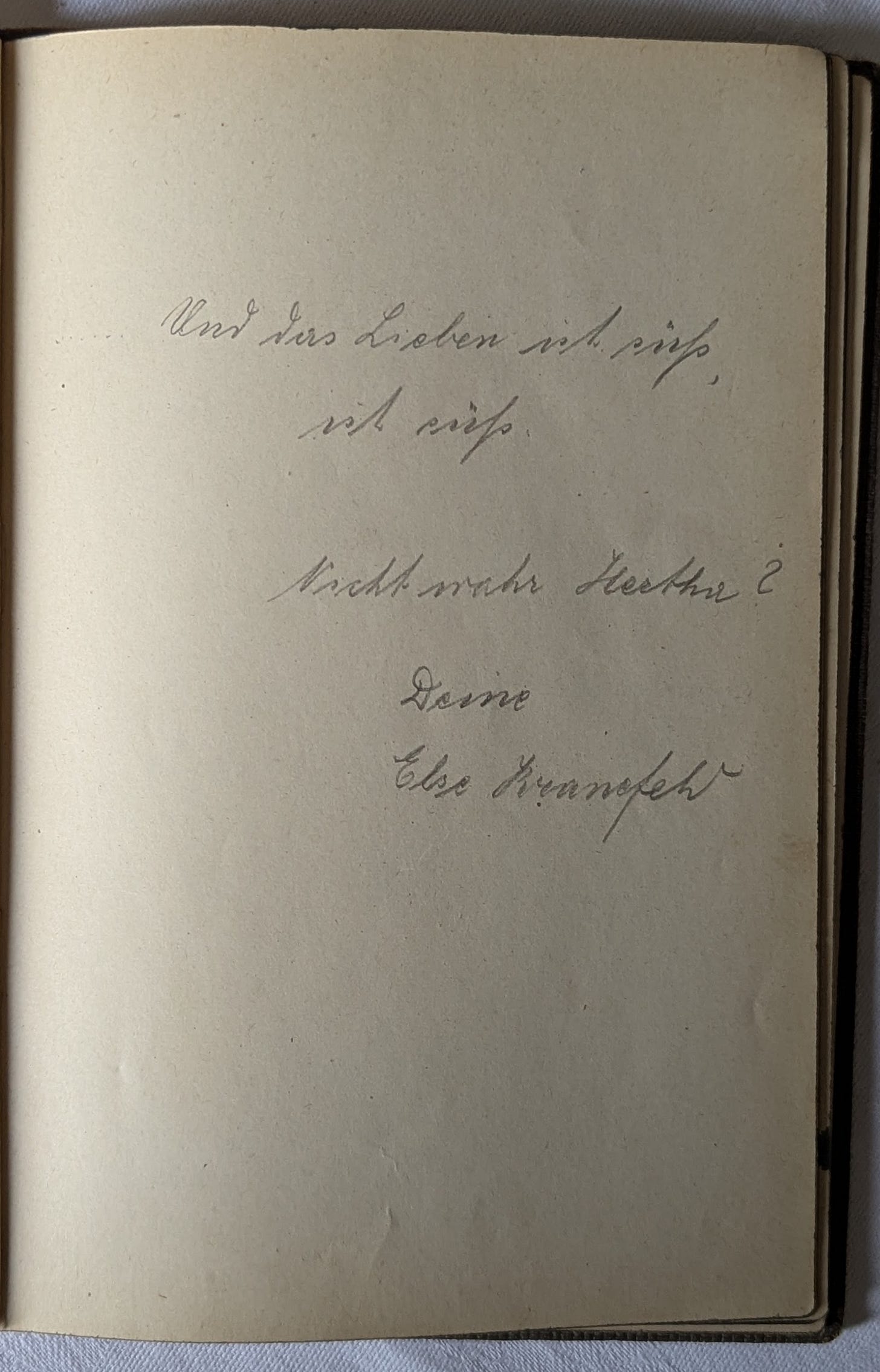

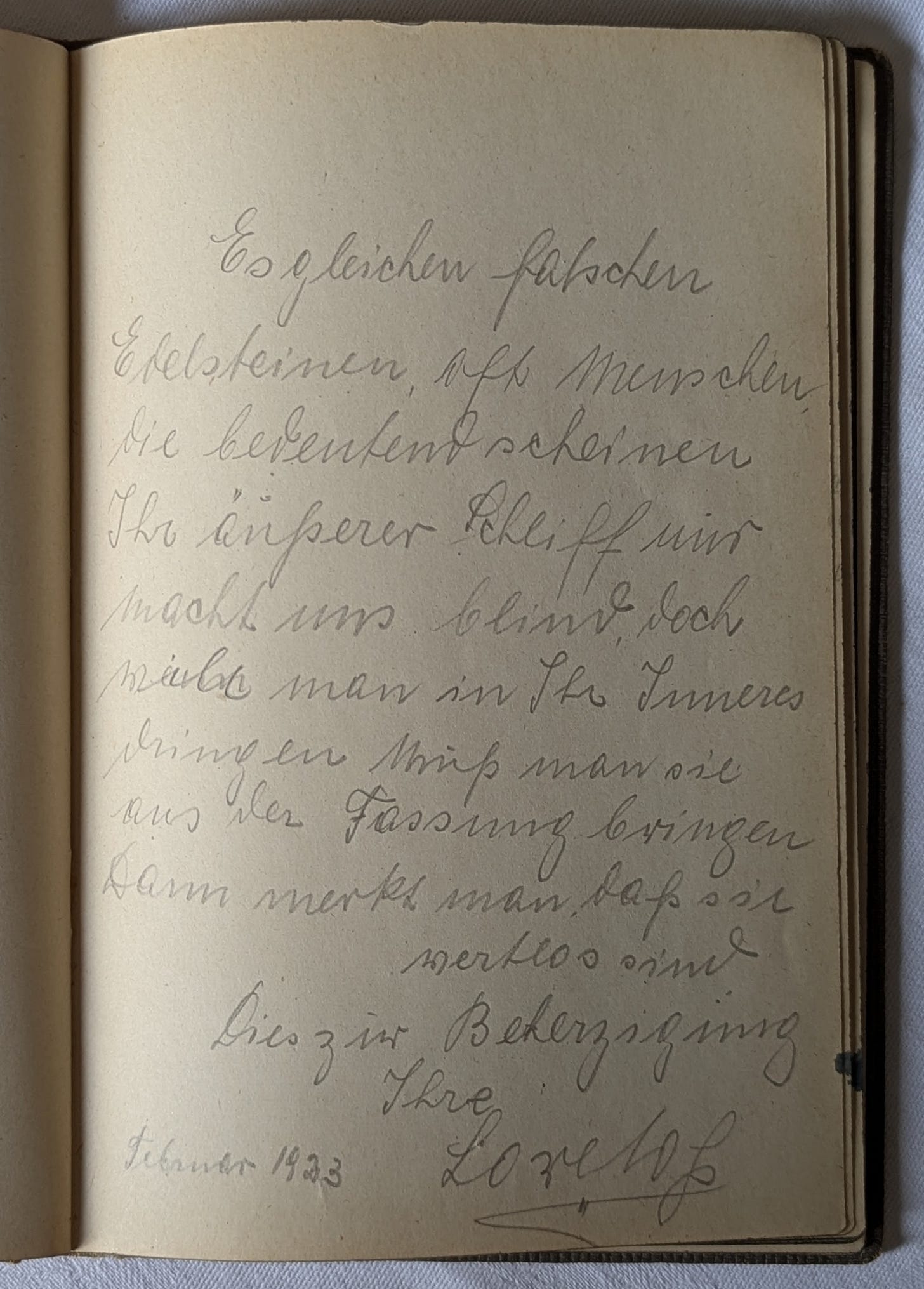

Here’s the Poesie album in full.

If you’re interested, here is a nicely-written dive into another poesie album from the Netherlands in the 1950s https://fanningsparks.com/my-cherished-poesie-album/

Research does lead one thing to another. I found a 250-page 2009 book written by Alfred Hintze: Ohne Meldung Unbekannt Verzogen - Moved without notice to an unknown location. It’s a comprehensive record of life in Schwerte (Ergste was part of this larger town) under the Nazis. It’s actually online here. I haven’t read it, but I guess will have to.

Mentioned in Ohne Meldung Unbekannt Verzogen (Hintze, 2009)

Mentioned in Ohne Meldung Unbekannt Verzogen (Hintze, 2009)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hyperinflation_in_the_Weimar_Republic

This is so fascinating - and touching.

What a fascinating read - thank you for doing the homework and sharing it Seb.