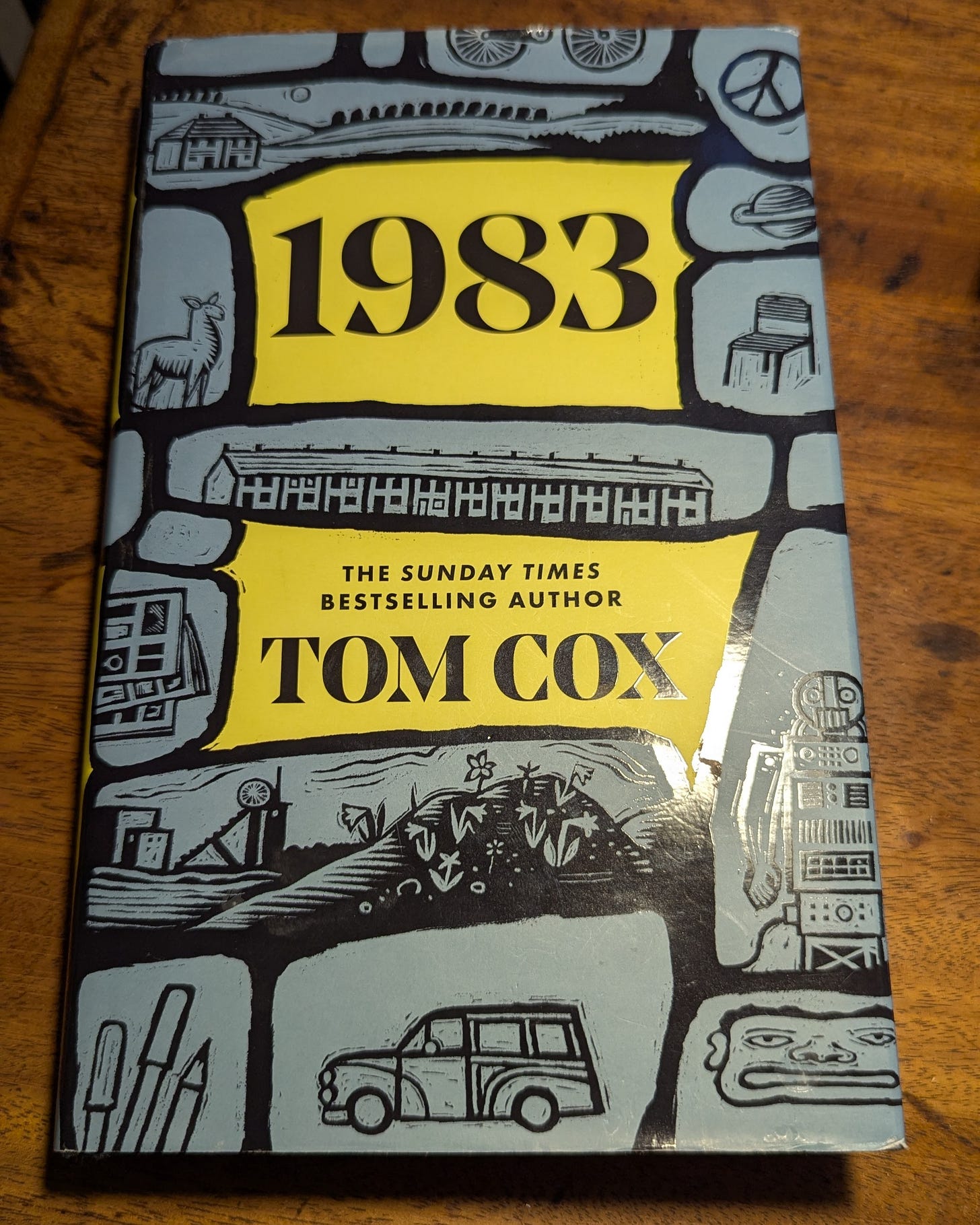

1983 by Tom Cox: Book Review

Whatever happened to white dog shit?

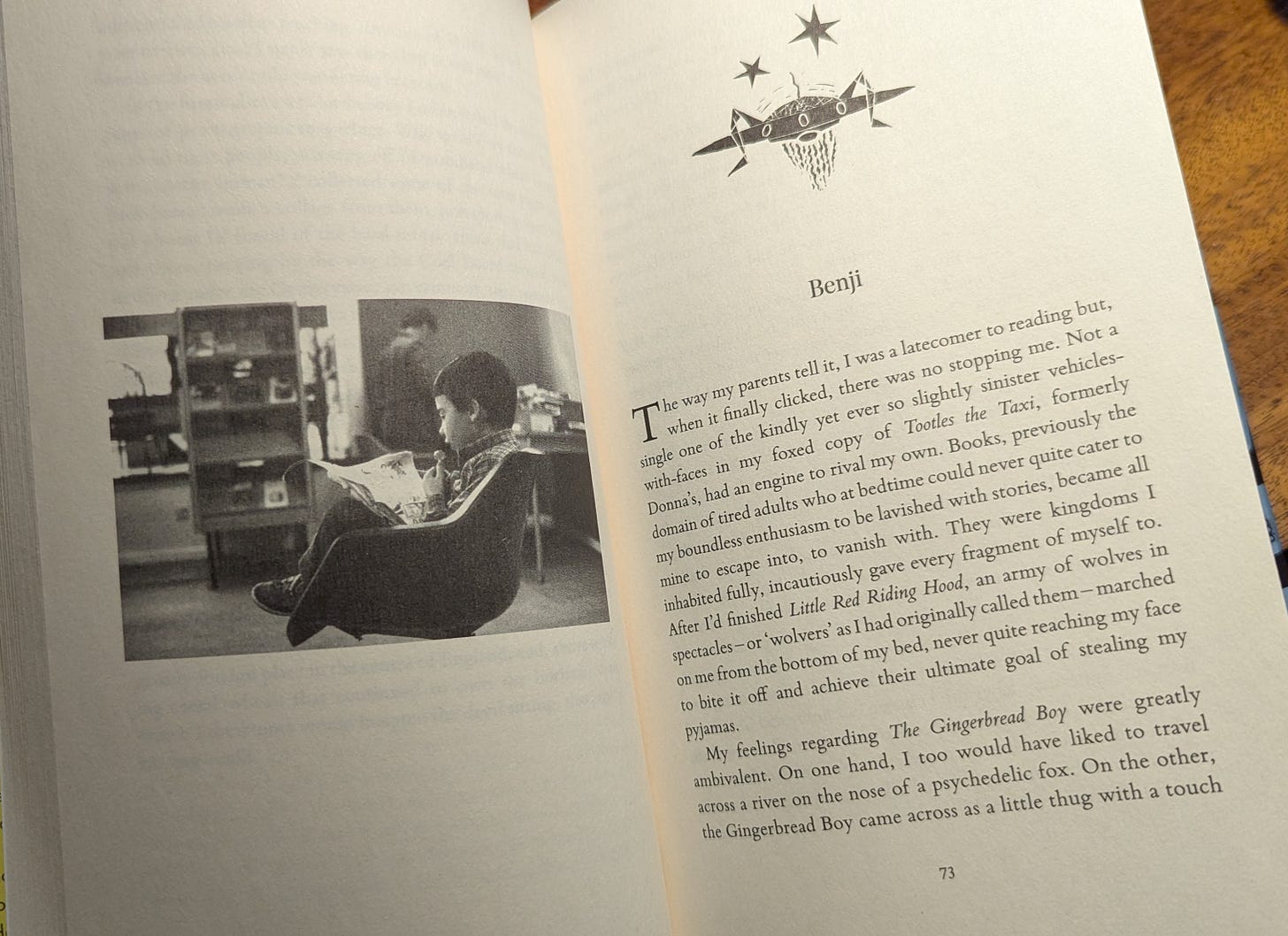

1983. Some time last summer this popped up in my Substack timeline: a new book, “1983” by Tom Cox. Isn’t it brilliant how Orwell’s year of ‘1984’, possibly chosen because he was writing in 1948, has such a strong cultural-psychic hold even if you’ve not read it, so much so that ‘1983’ or ‘1985’ make perfect sense as catchy book titles through proximity in a way that ‘1982’ or ‘1986’ probably wouldn’t. As I was in the middle of publishing my real-life, verbatim, as-it-actually-happened teenage diary from 1984 on Substack at the time (it’s now complete and you can read it here), and reliving memories of school, village life, girlfriends, dancing lessons, country hikes, and trips abroad as a seventeen-year-old, the book immediately piqued my interest. Here was another acount of life in rural England at the same time. The main character was Benji, an eight-year-old boy, based on Tom Cox’s own life. As a teenager one’s thoughts are developing in an interesting way, and one mediates the world in that intense teenagerish spirit. How would an eight-year-old’s memoir work? Could it be interesting enough? And it was a novel, not a memoir as such. These things all made me curious to read it. That’s quite apart from Tom Cox’s prodigious funny and touching and in-your-face Substack posts full of country-life, rants about publishers, entitled followers who post inappropriately, the music industry, great photos, and expletives, which have garnered him an impressive subscriber count. Who is this guy? Maybe the eight-year-old persona of Benji would give a clue.

Orwell’s 1984 does get name-checked towards the end of the book by Benji’s mum in a way that hints at a future loss of innocence. For Tom Cox’s story is partly about innocence, as Benji finds some kind of feet in an adult and, to some extent, alien world. And yes, I mean alien in that sense, you know, aliens. More of that later. In one grand reading the book could be said to be about the loss of some kind of supposed innocence that each generation experiences. “Luckily it doesn’t look like the world is actually going to be like that in the real 1984,” says Benji’s mum. We all breathed a fake sigh of relief in 1984, and then a real one 1989 when the Iron Curtain fell. But now?

However, that’s not the starting point and although you don’t need to get all philosophical reading this book, some aspects of it, say talking daffodils, yes talking daffs, lead you to the view that it’s a book about ideas as much as stuff that happened: about perspectives, and how we see things, and how we see things differently, about how we remember, or forget, things and how we construct worldviews and narratives and history and therefore bearing on politics and the future directions of the world. So, yes, grand in its own way.

The starting point is the very real world specifics of 1983. In a small town and village in middle England. In a specific, and rather interesting, unconventional family, with a dad who’d painted a blue Matisse nude on a wall in his flat. And very quickly the specifics start piling on thick and fast, things, brands, music, programmes we watched and things we did and said, little icons that lead us through present reality to time travel to a different age. I laughed at long forgotten items, and shared interpretations. The book is stuffed full of them. Here’s a few: dungarees, ZX Spectrum computers, microfiche, Ford Escorts (there are plenty of cars), Smash Hits, the Dennis the Menace fanclub, being terrified by the film Watership Down (in 2022, re-rated PG after 44 years), Margaret Thatcher (and being terrified by her maybe), Greenham Common (and being terrified of nuclear war - there were lots of things that could terrify a youngster), finding shredded porn mags, the Archers, “which made my dad swear sometimes and had a theme tune that made you think lots of fast and exciting things would happen in it even though nothing ever did”. And on and on. To be fair, like much in England a lot of these things, famously the Archers, just carry on forever, though the action has stepped up significantly in the Archers 40 years on. For those who have vague memories of that time just a mere mention evokes a ton of associations. Enough to make you want your whole life not to flash by you at the moment of your passing: not all THAT stuff, I don’t want to remember that! For those youngsters who might read the book, digital natives, Gen Z, and the like, kids who don’t know what an Austin Princess (later version, discontinued in ’81) looks like or how to play Dungeons & Dragons, there’s always Google to look up these references in an instant, or just be carried along by the surprising turns in this extraordinary book.

There is one thing I will myself google, though. White dog shit. Whatever happened to white dog shit? Yes, that was a big thing in the 80s. When Margaret Thatcher launched her pick up litter campaign in 1986 you used to see loads of it. At least that is my memory, let’s compare. Where’s that all gone now? It makes you look back fondly, but also question your assumptions of normal. Has dog nutrition changed for the better? Is Ultra Processed Dog Food (UPDFs) just as bad for them as humans? Is it the effect of climate change? What does it mean?

There’s more than enough in the book for English 1980s nerds, which is possibly a niche market. But if there’s not a bunch of people eager to find out about 1983 And All That, then there are the loveable characters, both real and imagined. For the book is not only about Benji. In the style of Orhan Pamuk’s ‘My Name Is Red’, each chapter gets its own narrator voice and perspective. His cousin particularly starts to come to the fore. Friends, teachers, neighbours, feature. One chapter starts with local chap Colin wondering “When was love invented?” and they all go off on detailed reminiscences. I found my allegiances as a reader shifting between characters. We need all the perspectives to make sense of what each individual character might be experiencing and to understand the (compared to today) slightly-more-pressured-life-than-we’d-all-like. But even with multiple perspectives, can we really interpret our lives? To have a truly objective view of the human story you’d need say the view of, I dunno, a plant. So at some point, the daffodils start to speak, and bemoan their lot. And the aliens that are part of Benji’s imagined world actually show up, and try to understand us. They turn out to be rather emotionless, technical, good-at-copying aliens, but I warmed to them. They ask us to take an outside view of events and culture - as much as we can - but also remind us that as humans we are emotionally invested in our specific pasts and contexts and our memories and quirks and silly ways of doing things, and that’s a good thing, because otherwise, well, you’d be an alien. It’s an artificial construct in a book full of real actual photos, but any time we start to process our memories, histories, narratives, it is only a construct. If at the time it was all happening, we wrote overly-interpretive diaries, we would be in danger of rationalising or distancing ourselves from ourselves and others. Sometimes we need to experience, and later reflect in order to narrate, and the process is different for everyone. “I always remember plants and flowers. It’s just the way my mind works”, says Benji’s mum. We don’t live life as it happens in similes and metaphors. I’ve never walked into town thinking, “the city feels like the bottom of a glass that too many people have been drinking from”. But maybe I should; maybe we could use language to enrich our mostly mundane lives as they happen; maybe Tom Cox (Tom Cox) does. Maybe that’s what we’re all doing here on Substack.

The aliens, who are able to shape-shift, turn out, pleasingly, to be rather incompetent. One of them ends up falling in love with an alpaca (by the time you get this point in the book, you’ll be good with this, promise) and disobeying orders to return to the mothership. And maybe this is the answer to why Orwell’s ‘1984’ didn’t materialise on earth the next year, why the Soviet Union collapsed, why dictators still do fall – simply because we’re not quite competent enough to impose a total system forever, and some of us disobey orders, fall in love, and have ideas of our own… Maybe AI will have better luck.

There is no system. There is no one truth. There is no one style. Tox Cox on Substack often says he writes as he wants to write, free from the helpful guidance of publishing houses. So it’s no surprise that 1983 is also full of contrasting styles. First person memoir, and sci-fi. Regular narrative, and chapters written like a play script. Sweetness and swear words. Why not? There is not one way of writing a novel. But through it all are the real photos (some reproduced a little more darkly than one would like) of real people from 1983, reminding us that this is after all a human story. Though daffodils exist, and maybe somewhere aliens, only humans, who have all passed through the age of eight, can take memories and turn them into stories and sometimes books that help us to value both the amazingness of humanity in general but more importantly the particularities of our lives, without which we would be mere robots.

I think l enjoyed your review of 1983 almost as much as the book! What really held me spellbound though, was 'Maybe we could use language to enrich our mostly mundane lives as they happen. Maybe Tom Cox does. Maybe that's what we're all doing here on Substack' That just summed it up so succinctly for me.

Really great review! ☺️